Thank you, Henrietta!

“It’s nothing serious,” Henrietta Lacks said to calm down her husband, David, and the children. The doctors just wanted to examine her one more time and give her a little medicine. It was February 5, 1951. Henrietta had just heard on the telephone that the nodule on her cervix was malignant.

She had no idea that she would go down in the history of medicine the following morning. David drove her to the gynecological department of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. They did not decide to travel such a distance because of the clinic’s good reputation. It was the only institution in the surroundings that treated Black people.

For Henrietta, it was a journey to an unknown land. For the first time, the vivacious woman heard terms like “cervix” and “biopsy.” But Henrietta, a young mother of five children, could barely read or write. She now found herself in the hospital ward for “colored women”, where none of the gods in white made any effort to explain what they were doing to the patients.

In the operating room, the surgeon on duty sewed a small tube with radium to her cervix—at the time the most modern therapy for treating cervical cancer. But before doing so, he cut out two coin-sized pieces of tissue and sent the samples to the laboratory of the scientist George Gey.

Gey had dedicated himself to the search for cells that could be multiplied again and again and was collecting samples. If he could manage to cultivate cells in a cell culture, it would then soon also be possible to conquer diseases like cancer, or so he hoped. Up to that point in time, however, every cell in the lab had had only an extremely limited life span. These cells would not survive very long either, thought Gey’s assistant.

“No dearth of clinical material”

No one had asked Henrietta whether she wanted to put her cells at the disposal of research. The idea would never have occurred to her physicians. “Hopkins, with its large indigent black population had no dearth of clinical material,” Howard Jones, Henrietta’s doctor once wrote. If the treatment was free of charge, the patients should at least benefit research.

Henrietta’s cells not only survived—as long as they received sufficient nutrients, they divided every twenty-four hours. And they were anything but delicate. Thanks to Henrietta’s suffering, George Gey found a reliable tool for modern medicine: the first immortal human cell line. He enthusiastically sent samples with the label HeLa (the first letters of the name Henrietta Lacks) to laboratories around the world.

Even though they are cancer cells, they share many basic characteristics with healthy cells: how the genes function, the production of proteins, the nutrient balance of a cell. HeLa assisted in the development of a vaccine against poliomyelitis. The cells have been infected with mumps, measles, chickenpox, herpes, tuberculosis, HIV, and, finally, the coronavirus. They have been exposed to powerful radiation in nuclear bomb tests and to zero gravity in outer space. The first clone was also a HeLa cell.

Good fortune for research, a tragedy for the family

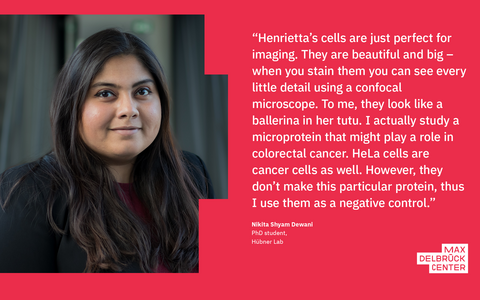

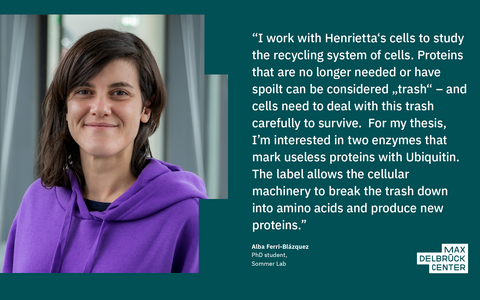

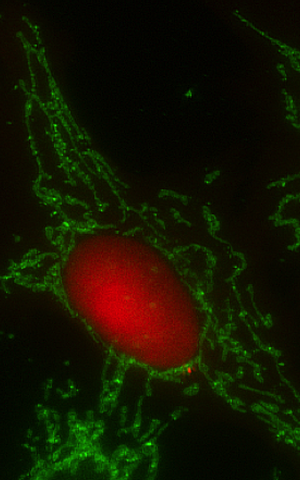

HeLa cell with 40-fold magnification: The cancer cells are modified by fluorescent proteins, they clearly show the nucleus in red and the mitochondria in green. Henrietta’s cells still supports our studies on the mitochondrial network.

It was also a HeLa cell that had been dyed inadvertently that facilitated a view of the forty-six human chromosomes. The list is almost endless. If it were possible to stack up all the HeLa cells that have ever been cultivated, they would weigh a total of more than fifty tons. If lined up one after the other, they would span the planet Earth three times. More than 75,000 studies have been created. Roughly 11,000 patents worldwide are based on HeLa. And countless scientists continue to use these cells—also at the Max Delbrück Center.

What was good fortune for research was a tragedy for the Lacks family. The tumor cells ate away at Henrietta’s body. The pain was so unbearable that the children were no longer allowed to visit her. David took them to play on the side of the street that Henrietta was able to see from her window. She could thus at least bid farewell to them from a distance. She died on October 4, 1951.

Twenty years went by before the family heard about HeLa. While millions of individuals owe their lives to Henrietta Lacks, her descendants could not even afford medical care. It is injustices like this that drive the WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. In 2021, he invited the Lacks family to Geneva and presented them with the medal of the Director-General of the World Health Organization. A recognition by humankind of Henrietta’s legacy—after seventy years.

“What happened to Henrietta was unjust. She was exploited,” said Tedros. She would surely be pleased by all the progress in medicine. “But the end does not justify the means. The doctors should have asked for her permission. Today, we have to at least acknowledge that it was wrong. And we must show solidarity with marginalized patients around the world.”

In Africa, a particularly large number of women die of cervical cancer

Skin color, ethnicity, money, and incidental place of birth still influence how well protected from illness a person is and how well one will be cared for in case of emergency. One example: the cervical cancer that killed Henrietta can be prevented by the vaccine against human papillomaviruses (HPV). Her cells paved the way for its development. But while teenagers in nearly all industrialized nations can decide whether or not they would like to be vaccinated, the HPV vaccine is available in just one fourth of the poorest nations. Of the twenty countries where the greatest numbers of young women die of cervical cancer, nineteen are located in Africa.

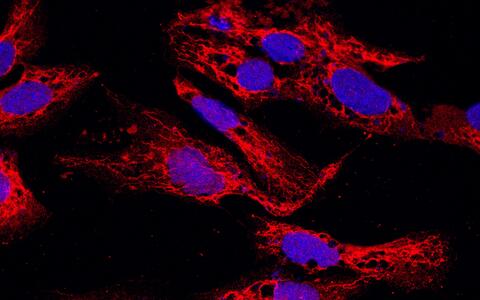

Imaging HeLa: In this picture, cell nuclei are stained in blue, mitochondria in red.

“We owe it to Henrietta to change this,” said Dr. Nono, Princess Nothemba Simelela, who is responsible for strategic focuses like women’s health at the WHO. “All people should have equal access to medical breakthroughs facilitated by HeLa cells,” Victoria Baptiste, who is herself a nurse and a great-granddaughter of Henrietta Lacks, also stresses. “Her legacy lives on in us. Thank you for saying her name: Henrietta Lacks.”

Text: Jana Schlütter

Weiterführende Informationen

- The Henrietta Lacks Initiative

- WHO-Zeremonie für Henrietta Lacks: Recognizing Her Legacy Across the World

- Rebecca Skloot: „Die Unsterblichkeit der Henrietta Lacks“. Irisiana, München.