“Too much communication is better than too little”

About our “We at the MDC” series

The MDC aspires to provide all employees with an attractive work environment – through an outstanding infrastructure and through collaboration with leading researchers, but also by being a place where tolerance, respect, and good interpersonal relations are paramount. It doesn’t always succeed in equal measure at attaining these aims. Our series introduces you to people who are engaged in this field. It also sheds light on internal processes that seek to ensure a positive organizational culture. And it provides tips for an attentive togetherness.

Read more about the series “We at the MDC”.

Why did you take on the role of ombudsman?

In 2014, the PhD researchers asked me if I would be willing to serve as their point of contact. Daniela Panáková and I took over the position from Thomas Sommer. We thought it made sense to have both a male and a female ombudsperson.

One often reads reports of staff mismanagement in science. How would you describe the leadership culture at the MDC?

This really varies. There are research groups with more traditional approaches, in which PhD students are regarded more as lab workers who do the detail work as instructed by the PI. On the other side of the spectrum are groups in which the coaching approach prevails, which I personally subscribe to. But this approach also cuts both ways. If you give your staff too much freedom, it can also be interpreted as a lack of supervision. When PhD students complain that supervision is not optimal, one therefore has to ask what they mean by that. There are some students who are dissatisfied if results aren’t discussed every other day, while for others this would feel like a surveillance state.

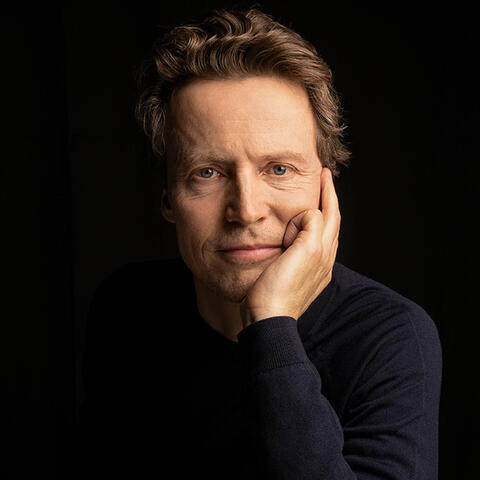

Prof. Dr. Matthias Selbach serves as ombudsman at the MDC.

When conflicts arise, the ombudspersons are the first point of contact for the PhD students. Do you have office hours?

No, we directly approach PhD students and let them know that we are there for them. Our contact details are also in the information materials that every new PhD student receives. Our message is: Contact us anytime! Too much communication is better than too little. Our role means we’re on their side. I usually receive an email asking for an appointment and then we meet shortly thereafter. This occurs approximately every two months. However, many young scientists struggle with a psychological barrier that prevents them from seeking help about their problem. That doesn’t have to be the case. Whatever is discussed remains confidential.

What are typical problems?

Sometimes a project is not progressing as well as it should, and the research group leader has a different idea about what should be done. In such cases, we offer a kind of external coaching – an unbiased opinion. This is possible because we know how research is carried out and understand the environment. Such external advice is important, and is hard to come by: One’s colleagues in the lab might have their own interests at heart and personal friends don’t understand the environment. In other cases, the issue at stake is one’s contribution to a project, including with regard to publications: For example, who is the lead author? But there are also very human problems that arise in the researchers’ dealings with one another – just like any other place where people work together. On top of that, the scientific world is very competitive. We try to help in all these situations.

What do you do specifically?

There’s a basic premise: Nothing is done that the PhD student explicitly doesn’t want to do. We talk and decide together the most sensible course of action. Often I first talk directly with the relevant research group leader and try to offer a new perspective. Or we gather all parties around a table to work out a solution. Whether in the end everyone agrees with the solution is another matter. But it’s generally best if conflicts are addressed as early as possible – before the situation has escalated. Sometimes it’s just a misunderstanding or just different perceptions that cause things to get out of hand. When a conflict hardens, personal accusations tend to arise. Then it becomes really difficult.

What happens if positions have already hardened?

We are not professional mediators, psychologists, or conflict managers, but instead the first point of contact. For example, we are not responsible for workplace law issues – or patent disputes. We can’t advise on these issues. But if the PhD student wants us to, we will bring the matter to the attention of the relevant persons and provide – if desired – further guidance along the way. If, for example, a student is suffering major psychological stress, we can facilitate initial contact with a psychologist. If there is a possibility that the rules of good scientific practice were violated, then Jens Reich, the Research Ombudsman, is the right person to contact. I would definitely recommend it. Such matters must be looked at systematically; PhD students are not in a position to do that on their own.

It’s sometimes necessary to come out in the open and make a formal complaint that clearly explains the problem. Otherwise the matter ends with the parties saying “We’ll talk about it.” Whatever the case may be, it is helpful and important for there to be a point of contact who is independent from one’s own research group.

We want to create a good environment

PhD students are always in a dependent relationship. Their actions are necessarily influenced by this circumstance.

Yes, it is indeed a difficult situation. But we aspire to provide PhD students at the MDC with a good work environment – not only in terms of research and technology, but also in terms of the human factor. We want them to be able to bring their work to a successful conclusion. If circumstances do not allow PhD students to continue research in their group, they may elect to change research groups. Sometimes separating is the better solution, even if such a decision doesn’t come easy – because it often unfortunately results in the PhD students losing time.

Are there mechanisms in place to mitigate the power imbalance?

There is, for example, the thesis committee. In addition to the PhD candidate and the lead supervisor, it consists of at least two other persons whom the candidates choose themselves. This committee accompanies PhD students throughout the thesis process, tracks their scientific progress, and provides advice and guidance. It looks at both sides, which includes a review of the supervisor, and meets at least three times. A portion of these meetings are conducted alternately without the PhD candidate and without the supervisor. I think this is very important. It provides another opportunity to address problems without the research group leader being present.

It’s similar to a status update?

Yes, exactly. Where am I now? What really important things still need to be done to reach my goal? Sometimes the committee makes strategic decisions together: “O.K., that’s two promising approaches, but there’s only enough time left to pursue one of these – we suggest that you focus on this one.” There is a coaching aspect to it, which is independent from the supervisor and his or her interests. We also have structured PhD programs that offer additional opportunities. These include scientific and research-related seminars and courses for which credit points are awarded – PhD students should be able to expand their scientific horizon and are thankful to have these opportunities.

Is the MDC’s leadership culture a generational issue?

It seems like it is. But there are anomalies where it’s actually the other way around. I believe the determining factor is ultimately the personality of the research group leader. Ideally, one’s style of leadership would be tailored to the individual needs of each PhD student. Some need pushing, some need holding back, while others need lots of praise and yet others need to be motivated. That’s the art of it. This, of course, doesn’t always work out in practice. I personally believe that the PhD students are here because they are eager and ambitious to pursue their own research – and that their drive comes from within themselves. Therefore, in my role as a research group leader, I don’t exert a lot of pressure. However, this might not be the best approach for all students. Some would achieve better results if more pressure were put on them.

Can one learn to be a good leader?

There are courses available for management staff, such as those offered by the Helmholtz Leadership Academy. Junior research group leaders at the MDC are assigned a mentor. Such opportunities are helpful. Most staff members who take advantage of these tend to be open to such issues. Those who consider such training to be nonsense will not participate, even if they needed it.

What do you hope to see at the MDC?

It is very important that the MDC offers group leaders good and regular training and that an atmosphere that fosters criticism and feedback is a natural, everyday part of the organization. Transparence is always a good idea – otherwise, rumors take over. An open dialogue should be maintained with all parties.

Jutta Kramm and Jana Schlütter conducted the interview.

Further information

You can reach out to the ombudspeople Matthias Selbach and Daniela Panáková at any time.