A big step toward producing rhino gametes

Thirty-three-year-old Najin and her daughter Fatu are the last surviving northern white rhinos on the planet. They live together in a wildlife conservancy in Kenya. With just two females left, this white rhino subspecies is no longer capable of reproduction – at least not on its own. But all hope is not lost: according to a paper published in the journal “Science Advances”, an international team of researchers has successfully cultivated primordial germ cells (PGCs) – the precursors of rhino eggs and sperm – from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

This represents a major milestone in an ambitious plan. The BioRescue project, which is coordinated by the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) and has been funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) since 2019, wants to save the northern white rhino from extinction. To this end, the scientists are pursuing two strategies – one of them trying to generate viable sperm and eggs from the skin cells of deceased rhinos. The idea is to implant the resulting embryos into closely related southern white rhino females, who will then carry the surrogate offspring to term. And so the northern white rhino subspecies, which humans have already effectively wiped out through poaching, may yet be saved thanks to state-of-the-art stem cell and reproductive technologies.

First success with an endangered species

To get from a piece of skin to a living rhinoceros may be a true feat of cellular engineering, but the process itself is not unprecedented: the study’s co-last author Professor Katsuhiko Hayashi leads research labs at the Japanese universities of Osaka and Kyushu in Fukuoka, where his teams have already accomplished this feat using mice. But for each new species, the individual steps are uncharted territory. In the case of the northern white rhinoceros, Hayashi is working in close cooperation with Dr. Sebastian Diecke’s Pluripotent Stem Cells Technology Platform at the Max Delbrück Center and with reproduction expert Professor Thomas Hildebrandt from Leibniz-IZW. The two Berlin-based scientists are also co-last authors of the current study.

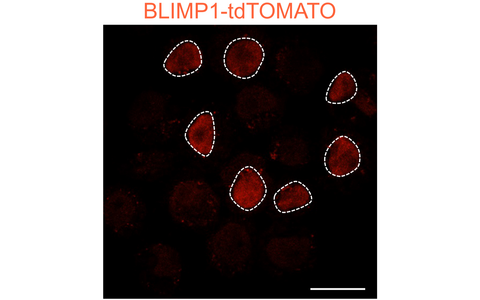

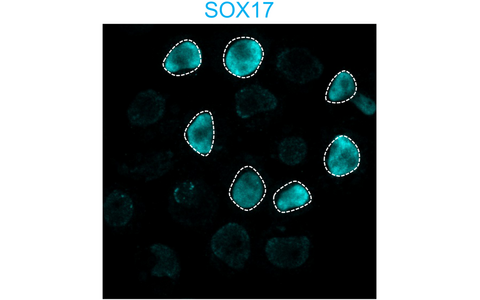

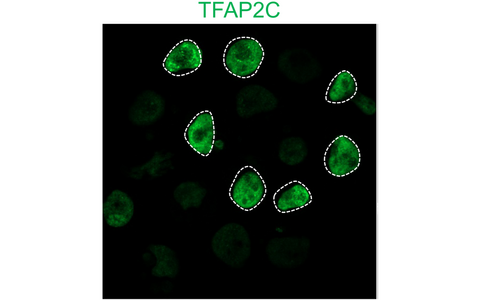

“This is the first time that primordial germ cells of a large, endangered mammalian species have been successfully generated from stem cells,” explains the study’s first author, Masafumi Hayashi of Osaka University. Previously, it has only been achieved in rodents and primates. Unlike in rodents, the researchers have identified the SOX17 gene as a key player in rhinoceros PGC induction. SOX17 also plays an essential role in the development of human germ cells – and thus possibly in those of many mammalian species.

The southern white rhino embryonic stem cells being used in Japan come from the Avantea laboratory in Cremona, Italy, where they were grown by Professor Cesare Galli’s team. The newly derived northern white rhino PGCs, meanwhile, originated from the skin cells of Fatu’s aunt, Nabire, who died in 2015 at Safari Park Dvůr Králové in the Czech Republic. Diecke’s team at the Max Delbrück Center was responsible for converting them into induced pluripotent stem cells.

Next step: cell maturation

We have to find suitable conditions under which the cells will grow and divide their chromosome set in half.

Masafumi Hayashi says that they are hoping to use the cutting-edge stem cell technology from Katsuhiko Hayashi’s lab to save other endangered rhino species: “There are five species of rhino, and almost all of them are classified as threatened on the IUCN Red List.” The international team also used stem cells to grow PGCs of the southern white rhino, which has a global population of around 20,000 individuals. In addition, the researchers were able to identify two specific markers, CD9 and ITGA6, that were expressed on the surface of the progenitor cells of both white rhino subspecies. “Going forward, these markers will help us detect and isolate PGCs that have already emerged in a group of pluripotent stem cells,” Hayashi explains.

The BioRescue scientists must now move on to the next difficult task: maturing the PGCs in the laboratory to turn them into functional egg and sperm cells. “The primordial cells are relatively small compared to matured germ cells and, most importantly, still have a double set of chromosomes,” explains Dr. Vera Zywitza from Diecke’s research group, who was also involved in the study. “We therefore have to find suitable conditions under which the cells will grow and divide their chromosome set in half.”

Dr. Vera Zywitza working in the laboratory.

Genetic variation is key for conservation

Leibniz-IZW researcher Hildebrandt is also pursuing a complementary strategy. He wants to obtain egg cells from 22-year-old Fatu and fertilize them in Galli’s lab in Italy using frozen sperm collected from four now deceased northern white rhino bulls. This sperm is thawed and injected into the egg in a process known as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). However, Hildebrandt explains that Fatu is not able to bear her own offspring, as she has problems with her Achilles tendons and cannot carry any additional weight. Her mother Najin, meanwhile, is past child-bearing age and also suffers from ovarian tumors. “And in any case, since we only have one donor of natural eggs left, the genetic variation of any resulting offspring would be too small to create a viable population,” he adds.

The team’s top priority, therefore, is turning the PGCs they now have at their disposal into egg cells. “In mice, we found that the presence of ovarian tissue was important in this crucial step,” Zywitza explains. “Since we cannot simply extract this tissue from the two female rhinos, we will probably have to grow this from stem cells as well.” The scientist is hopeful, however, that ovarian tissue from horses could come in useful, as horses are among the rhinos’ closest living relatives from an evolutionary standpoint. If only humans had taken as good care of the wild rhino as they had of the domesticated horse, the immense challenge now facing the BioRescue scientists could perhaps have been avoided altogether.

Additional quotes

Katsuhiko Hayashi, Osaka University:

“Developing a culture system that delivers robust results has been extremely challenging since the precise orchestration of the specific signals required to induce the desired cellular differentiation is unique to every species. It was also necessary to confirm that the primordial germ cell-like cells were genetically identical to the cells from which they originated – this can be a daunting task.”

Jan Stejskal, Safari Park Dvůr Králové:

“We are thrilled that the BioRescue scientists have achieved this milestone and that Nabire, who died in 2015 in Dvůr Králové, is still able to help save her species. Unfortunately, she didn’t have any offspring during her life, but recent successes in stem cell associated techniques have shown that it is perfectly possible that a direct descendant of Nabire will be born at some point in the future and can play an important role in repopulating central Africa with northern white rhinos.”

Thomas Hildebrandt, Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research:

“We knew from the beginning that advanced assisted reproduction technologies that rely on natural gametes would not be sufficient in the long run to save the northern white rhino from the brink of extinction. So it is crucial that we pursue a complementary strategy of significantly increasing the genetic diversity of gametes and of producing them in much greater numbers – which might even make it possible to create embryos from Najin through artificial gametes, something that proved to be impossible using her natural gametes. It is encouraging to see that the stem cell specialists in our consortium, from Osaka University and the Max Delbrück Center, have achieved this important milestone. It is also important to note that the plans for natural gametes and artificial gametes are not separate paths, but are interconnected and intersect at the point where in vitro fertilization produces embryos.”

Cesare Galli, Avantea:

“In 2018, Dr. Giovanna Lazzari of our lab successfully derived embryonic stem cells (ESCs) from the first southern white rhino embryos that we were able to obtain. This proved to be instrumental for the success of the work of Professor Hayashi’s team because ESC have been studied and differentiated for a long time and provided a template for the iPSCs.”

Further information

- BioRescue consortium

- Katsuhiko Hayashi, Professor in the Department of Stem Cell Biology and Medicine at Kyushu University in Japan

- Department of Reproduction Management at Leibniz-IZW

- A second chance for the Sumatran rhino

- One step closer to artificial rhino eggs

- Rhinos from skin cells

Literature

Masafumi Hayashi et al. (2022): “Robust induction of primordial germ cells of white rhinoceros on the brink of extinction,” Science Advances, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abp9683

Downloads

The last two surviving females live in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. Photo: Jan Stejskal, Safari Park Dvůr Králové

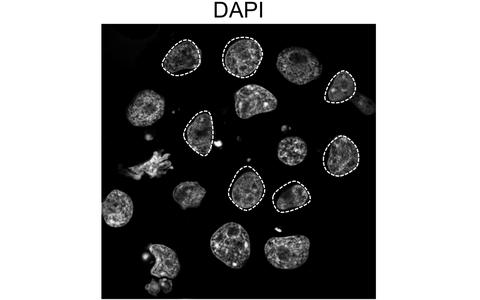

The SOX17 gene played a key role in inducing primordial germ cells from pluripotent stem cells of the white rhinoceros. Photo: Masafumi Hayashi, Osaka University

The graphic outlines the researchers’ plan (A), shows day 4 of the induction of primordial germ cells from rhinoceros pluripotent stem cells (B), and a comparison of the gene expression profiles of these cells in humans, mice, and southern white rhinoceroses. Cell differentiation proceeded similarly in humans and rhinos. Here, embryonic stem cells of the southern white rhinoceros were used (C). Graphic: Masafumi Hayashi, Osaka University

Contacts

Masafumi Hayashi

Osaka University

mhayashi@gcb.med.osaka-u.ac.jp

Prof. Katsuhiko Hayashi

Osaka University and Kyushu University

hayashik@gcb.med.osaka-u.ac.jp

Dr. Sebastian Diecke

Head of the Pluripotent Stem Cells Technology Platform

Max Delbrück Center

sebastian.diecke@mdc-berlin.de

Jana Schlütter

Editor, Communications Department

Max Delbrück Center

+49-(0)30-9406-2121

jana.schluetter@mdc-berlin.de or presse@mdc-berlin.de

Prof. Thomas Hildebrandt

BioRescue project head and head of Department of Reproduction Management

Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW)

+49-(0)30-5168-440

hildebrandt@izw-berlin.de

Jan Zwilling

Science Communication

Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW)

+49-(0)30-5168-121

zwilling@izw-berlin.de

Jan Stejskal

Director of Communication and International Projects

Safari Park Dvůr Králové

+420-608-009-072

jan.stejskal@zoodk.cz

Prof. Cesare Galli

Managing Director

Avantea, Laboratory of Reproductive Technologies

+39-(0)372-437242

cesaregalli@avantea.it

- Max Delbrück Center

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (Max Delbrück Center) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 70 countries study human biology – investigating the foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium of a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should be able to benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. This is why the Max Delbrück Center supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly-run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the Max Delbrück Center today employs 1,800 people and is 90 percent funded by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.