3D maps of gene activity

Professor Nikolaus Rajewsky is a visionary: He wants to understand exactly what happens in human cells during disease progression, with the goal of being able to recognize and treat the very first cellular changes. “This requires us not only to decipher the activity of the genome in individual cells, but also to track it spatially within an organ,” explains the scientific director of the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB) at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) in Berlin. For example, the spatial arrangement of immune cells in cancer ("microenvironment") is extremely important in order to diagnose the disease accurately and select the optimal therapy. “In general, we lack a systematic approach to molecularly capture and understand the (patho-)physiology of a tissue.”

Maps for very different tissue types

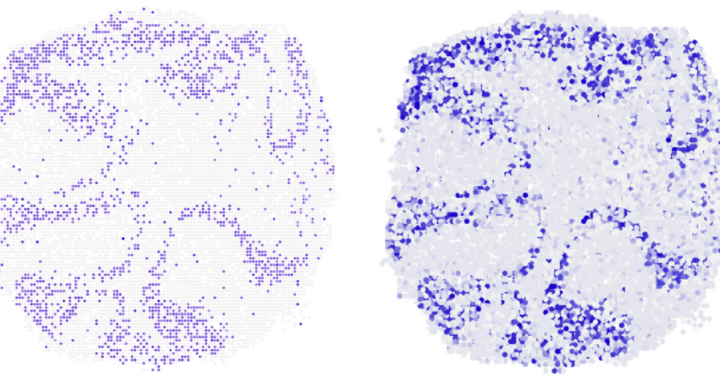

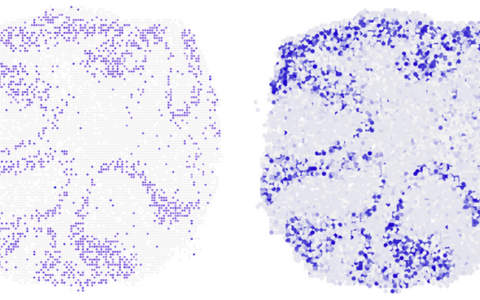

Where in the mouse cerebellum is the gene Neurod1 being transcribed? The vertical section shows that novoSpaRc (right) is able to answer this question very reliably on the basis of available single cell sequencing data. On the left for comparison the result of experiments.

We need to invest a lot more in machine learning and artificial intelligence.

Rajewsky has now taken a big step towards his goal with a major new study that has been published in the scientific journal Nature. Together with Professor Nir Friedman from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Dr. Mor Nitzan from Harvard University in Cambridge, USA, and Dr. Nikos Karaiskos, a project leader from his own research group on “Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements”, the scientists have succeeded in using a special algorithm to create a spatial map of gene expression for individual cells in very different tissue types: in the liver and intestinal epithelium of mammals, as well as in embryos of fruit flies and zebrafish, in parts of the cerebellum, and in the kidney. “Sometimes purely theoretical science is enough to publish in a high-ranking science journal - I think this will happen even more frequently in the future. We need to invest a lot more in machine learning and artificial intelligence,” says Nikolaus Rajewsky.

“Using these computer-generated maps, we are now able to precisely track whether a specific gene is active or not in the cells of a tissue part,” explains Karaiskos, a theoretical physicist and bioinformatician who developed the algorithm together with Mor Nitzan. “This would not have been possible in this form without our model, which we have named ‘novoSpaRc.’”

Spatial information was previously lost

NovoSpaRc enables a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle of gene expression.

It is only in recent years that researchers have been able to determine – on a large scale and with high precision – which information individual cells in an organ or tissue are retrieving from the genome at any given time. This was thanks to new sequencing methods, for example multiplex RNA sequencing, which enables a large number of RNA molecules to be analyzed simultaneously. RNA is produced in the cell when genes become active and proteins are formed from their blueprints. Rajewsky recognized the potential of single-cell sequencing early on, and established it in his laboratory.

“But for this technology to work, the tissue under investigation must first be broken down into individual cells,” explains Rajewsky. This process causes valuable information to be lost: for example, the original location in the tissue of the particular cell whose gene activity has been genetically decoded. Rajewsky and Friedmann were therefore looking for a way to use data from single-cell sequencing to develop a mathematical model that could calculate the spatial pattern of gene expression for the entire genome – even in complex tissues.

The teams led by Rajewsky and Dr. Robert Zinzen, who also works at BIMSB, already achieved a first breakthrough two years ago. In the scientific journal Science, they presented a virtual model of a fruit fly embryo. It showed which genes were active in which cells in a spatial resolution that had never before been achieved. This gene mapping was made possible with the help of 84 marker genes: in situ experiments had determined where in the egg-shaped embryo these genes were active at a certain point in time. The researchers confirmed their model worked with further complex in situexperiments on living fruit fly embryos.

A puzzle with tens of thousands of pieces and colors

Can we learn a principle about how gene expression is organized and regulated in complex tissues?

“In this model, however, we reconstructed the location of each cell individually,” said Karaiskos. He was one of the first authors of both the “Science” study and the current “Nature” study. "This was possible because we had to deal with a considerably smaller number of cells and genes. This time, we wanted to know whether we can reconstruct complex tissue when we have hardly any or no previous information. Can we learn a principle about how gene expression is organized and regulated in complex tissues?” The basic assumption for the algorithm was that when cells are neighbors, their gene activity is more or less alike. They retrieve more similar information from their genome than cells that are further apart.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers used existing data. For liver, kidney and intestinal epithelium there was no additional information. The group had been able to collect only a few marker genes by using reconstructed tissue samples. In one case, there were only two marker genes available.

“It was like putting together a massive puzzle with a huge number of different colors – perhaps 10,000 or so,” explains Karaiskos, trying to describe the difficult task he was faced with when calculating the model. “If the puzzle is solved correctly, all these colors result in a specific shape or pattern.” Each piece of the puzzle represents a single cell of the tissue under investigation, and each color an active gene that was read by an RNA molecule.

.

The scientific question is like a puzzle for Professor Nikolaus Rajewsky and Nikos Karaiskos.

The method works regardless of sequencing technique

“We now have a method that enables us to create a virtual model of the tissue under investigation on the basis of the data gained from single-cell sequencing in the computer – regardless of which sequencing method was used,” says Karaiskos. “Existing information on the spatial location of individual cells can be fed into the model, thus further refining it.” With the help of novoSpaRc, it is then possible to determine for each known gene where in the tissue the genetic material is active and being translated into a protein.

Now, Karaiskos and his colleagues at BIMSB are also focusing on using the model to trace back over and even predict certain developmental processes in tissues or entire organisms. However, the scientist admits there may be some specific tissues that are incompatible with the novoSpaRc algorithm. But this could be a welcome challenge, he says: A chance to try his hand at a new puzzle!

Text: Anke Brodmerkel

Further information

Video presentation: “A puzzle with 37 trillion pieces”

Press release: “Tracking development cell by cell is ‘Breakthrough of the Year’”

PPress release: “Reconstructing life at its beginning, cell by cell”

Literature

Mor Nitzan, Nikos Karaiskos et al. (2019): “Gene expression cartography”, Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1773-3.

Contacts

Prof. Nikolaus Rajewsky

Head of the Lab “Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements”, Scientific Director of BIMSB

Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB) of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

rajewsky@mdc-berlin.de

Dr. Nikos Karaiskos

Postdoc und Project Leader in the Lab “Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements”

Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB) of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

Nikolaos.Karaiskos@mdc-berlin.de

Christina Anders

Editor, Communications Department

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

+49 - 30 – 9406 2118

christina.anders@mdc-berlin.deor presse@mdc-berlin.de

- The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the MDC’s locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 60 countries analyze the human system – investigating the biological foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium in a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. The MDC therefore supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the MDC today employs 1,600 people and is funded 90 percent by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.