A genetic chaperone for healthy aging?

Researchers at MDC’s Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB) have found a protein that has a significant impact on healthy muscles and lifespan. Animals lacking this protein, called LIN-53, have severe muscle defects, limited motility, and die early compared to animals with the protein.

Dr. Baris Tursun, who leads BIMSB’s Gene Regulation and Cell Fate Decision Lab, and his collaborators figured out two specific ways LIN-53 works in roundworms. Their findings, reported in the journal Aging Cell, lay the groundwork for further studies on the human version of the protein.

“Identifying the genetic factors that play a role in linking lifespan and healthspan is key for understanding human health and aging-related diseases such as muscular dystrophy,” Tursun said.

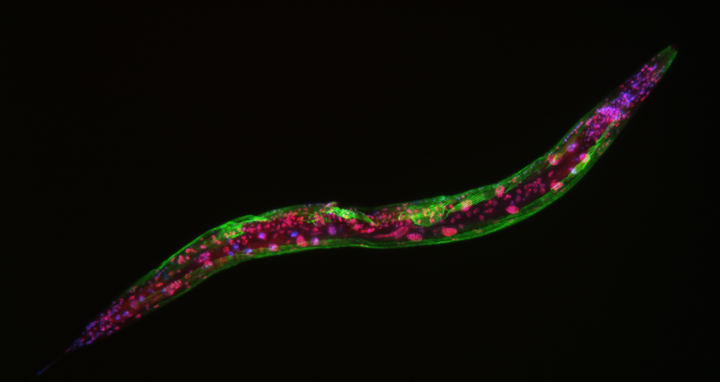

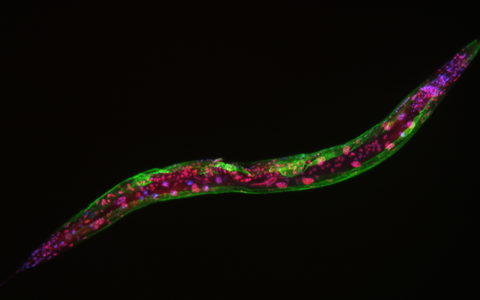

A C. elegans roundworm imaged with fluorescent markers. The green color highlights muscle tissue, while the red colors indicate LIN-53 proteins. This roundworm lacks the LIN-53 protein in its muscle tissues, which leads to defective muscles. Cell nuclei are stained with a blue/purple color.

Epigenetic factor

LIN-53 is not just any protein, it is a “histone chaperone,” binding to the molecules called histones that long DNA strands tightly wrap around to fit in the cell nucleus. Histone modifications can ultimately turn gene expression levels up or down, affecting an organism's development, function and lifespan. LIN-53 is considered an “epigenetic factor” because by interacting with histones, it can help activate and deactivate genes that can result in heritable traits passed to offspring, but without changing the underlying DNA sequence.

Tursun and his colleagues wanted to understand if this epigenetic factor influences how long an organism lives (lifespan), and how long an organism lives in a healthy state (healthspan). They also wanted to learn if lifespan and healthspan are directly related.

“Usually when we age, we experience aging symptoms accompanied by muscle loss,” Tursun said. “Is this all coincidence or is it linked, and if so, how it is linked? Our paper is one of the first to show an epigenetic link.”

One factor, two routes

The team of molecular biologists and geneticists investigated LIN-53’s role in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), a worm only 1 millimeter long. Also referred to as a nematode, it is one of the primary model organisms used in aging research because many of its genes are highly conserved, or found, across species.

“It is such a small organism and yet still resembles human tissues, pathways and gene regulation, so we are able to transfer results from the nematode to humans,” said Stefanie Müthel, first author of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher at the Myology Lab at the Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), a joint institution of Charité and the MDC.

When the researchers knocked out the gene for LIN-53, the worms showed reduced ability to move and did not live as long as counterparts with the gene.

This clearly indicated LIN-53 plays role in healthy muscles and lifespan. The team dug further and determined LIN-53 affects muscle development through the molecular complex NuRD, while it affects lifespan through a separate complex, Sin3. The fact that these are distinct pathways, but both involving LIN-53, is particularly intriguing and strongly suggests the importance of LIN-53 as a link between healthspan and lifespan.

“LIN-53 is part of seven different molecular complexes regulating chromatin modification and structure,” Müthel said. “I was surprised and excited that we were able to clearly define the complexes important for healthspan and lifespan.”

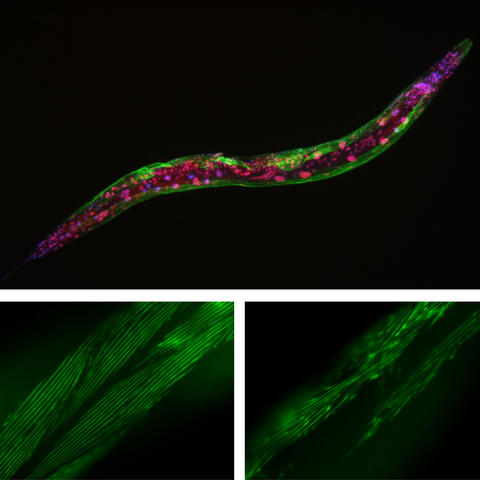

C. elegans roundworms without (right) the LIN-53 protein show irregular muscle fibers compared to roundworms with the protein (left). They also died, on average, five days sooner, indicating LIN-53 affects both health and lifespan.

The good sugar

Additional analysis revealed a possible explanation for why LIN-53 is so powerful. Animals without LIN-53 had very low levels of a sugar, called trehalose; it consists of two glucose molecules is known to be essential for normal lifespan in invertebrates. The interaction between LIN-53 and Sin3 affected genes that regulate metabolism, including the production of this sugar. Further research is needed to understand exactly how LIN-53 interacts with both NuRD and Sin3, and inhibits sugar production.

Since the LIN-53 protein is very similar to human protein RBBP4/7, researchers can use insights gained from the microscopic worms to guide where to look for answers to similar questions in humans.

“We all want to age in a healthy manner,” Tursun said. “Once we understand the links between aging and all the accompanying detrimental effects, then we can begin to think about how to unlink them.”

Laura Petersen

Further information

Literature

Stefanie Müthel et al. (2019): “The conserved histone chaperone LIN-53 is required for normal lifespan and maintenance of muscle integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans” Aging Cell, https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13012

Contacts

Dr. Baris Tursun

Head of the Lab “Gene Regulation and Cell Fate Decision in C. elegans” at the Berlin Institute of Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB)

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

+49 30 9406-1730

Baris.Tursun@mdc-berlin.de

Jana Schlütter

Editor, Communications Department

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

+49 30 9406-2121

jana.schluetter@mdc-berlin.de

- The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the MDC’s locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 60 countries analyze the human system – investigating the biological foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium in a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. The MDC therefore supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the MDC today employs 1,600 people and is funded 90 percent by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.