📺 Twitches of life from blood and silk

The room is filled with ambient sounds. Suspended from the ceiling is a ring-shaped apparatus. Visitors tilt back their heads to gaze through the round windows on its underside into the interior, where small, jelly-like creatures move with a twitching motion in a clear liquid. Living creatures?

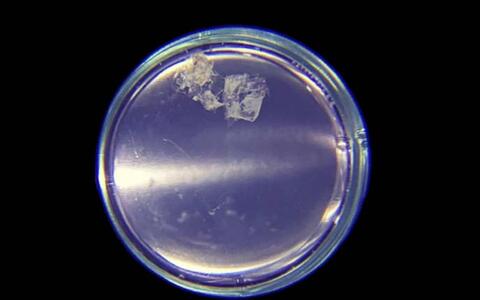

Not quite. The creators of this art installation – Australian artists Guy Ben-Ary and Nathan Thompson and German scientist Dr Sebastian Diecke – call them 'biological automatons'. They are made of human heart muscle cells which Guy Ben-Ary grew from induced pluripotent stem cells under the guidance of Sebastian Diecke and attached to support structures made of silk. In the incubator, the heart muscle cells grew on these delicate scaffolds to form three-dimensional structures that can be seen with the naked eye. They resemble little jellyfish, pulsing with a rhythm similar to a heartbeat. The artists and the scientist call their work Bricolage, and it was first exhibited on 6 February 2020 at the Fremantle Arts Centre in Western Australia. This French term means 'do-it-yourself'. In art, bricolage refers to works made of unexpected materials such as discarded rubbish, everyday objects or driftwood. Or in this case, human cells. In March, the work won the prestigious Award of Excellence at this year's Japan Media Arts Festival.

Bricolage - Video Documentation by Guy Ben-Ary

Somehow not of this world

Bricolage is not the first collaboration combining art and science between Ben-Ary and Diecke. In 2017, with Diecke's assistance, Ben-Ary created cellF, the world's first 'neural synthesiser', in Berlin. Sebastian Diecke leads the pluripotent stem cells technology platform, a joint endeavour of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). Ben-Ary has been involved for over 20 years with SymbioticA, a laboratory at the University of Western Australia in Perth where scientists and artists use art to explore the dimensions of science, its opportunities and its risks. For the cellF experiment the artist removed a piece of skin from his own forearm, reprogrammed the skin cells to become induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells), and then used them to grow nerve cells. These were linked up to a machine that converted the nerve cell impulses into sounds. At a concert in Berlin's Haus der Kulturen der Welt, a drummer set the neurons vibrating with a drum roll. The synthesiser then translated these vibrations into sounds that were somehow not of this world.

Sebastian and Ben, how did your collaboration come about?

Sebastian Diecke: Through a former member of staff at MDC who moved to a job in the arts. She approached me, told me about cellF and said that the artists were looking for someone who could help them with the official approvals. There are rules in place regarding stem cells – you can't just drive them around town. I found it fascinating – I never would have thought I'd be involved in something that crazy. cellF was simply intriguing, this extraordinary music emanating from the rhythmic impulses of the neurons. So when the next project came about, I got involved again immediately.

Scientists and artists aren't so very different, because they're both researchers.

Guy Ben-Ary: I can't remember exactly when we met. Someone introduced me to Sebastian and I found him remarkable. I've collaborated with a lot of researchers in my time, and in my world there are two types of scientist: those who are open towards artists and those who are not. Sebastian is very friendly and very generous. He didn't just help us with the organisational side of things; he supplied us with cells, he was always there for us, he shared his expertise with us, and in this way he made an essential contribution to the creation of Bricolage. That's why we credited him as a co-creator.

Scientists and artists don't speak the same language. Do you ever have communication problems?

Sebastian Diecke: I find that Guy and I understand each other very well. He has a solid basic understanding of science. That isn't the case with every artist. Some are very detached in a certain sense, which makes it difficult to find a common denominator.

Guy Ben-Ary: Scientists and artists aren't so very different, because they're both researchers. It's not true that scientists are exclusively rational and artists are intrinsically creative. There are highly creative scientists and there are artists who can draw extremely well, but that doesn't necessarily mean they are creative. But it's true that scientists and artists follow different impulses. Sebastian tries to get to the bottom of mechanisms and understand why things are the way they are. He collects data and tries to make things experimentally repeatable. His intention as a scientist is to illuminate the fog. But as an artist, I like the fog. I do things that aren't repeatable, I exaggerate them. My research isn't scientific but cultural. But despite that, I don't have any communication problems with Sebastian. I know exactly what he means by 'detached'. I've been working at SymbioticA for 20 years and I know my way around cell cultures, tissue engineering and things like that. Artists from all over the world come to us, and many of them have some very unrealistic ideas. That's fine when they're developing their creative projects, but once they reach the point where they join forces with scientists, they need to know how the biological technologies that they want to use actually work. They also need to understand the ethical requirements that must be met for this kind of experiment. A lot of people simply don't do their homework in this respect.

I see art as a means of making the general public aware of our research work. To show what stem cells are and what they can be used for.

Sebastian Diecke: I was once contacted by an artist who wanted to grow meat from her own cells, which she then intended to eat during a performance. For me that crosses a line. In my view that's not art, but pure provocation, and not feasible for various ethical reasons. So I wouldn't get involved in something like that. I want to enlighten, inform and arouse interest, not just provoke.

Enlighten about what?

Sebastian Diecke: For one thing, I see art as a means of making the general public aware of our research work. To show what stem cells are and what they can be used for. For another thing, art is a good way of starting a conversation with people and stimulating a discussion. By showing what is technologically possible, you can also pose the question of how far science should be allowed to go. Whether it's OK to do everything that's possible, or whether there is a line somewhere that shouldn't be crossed.

Guy Ben-Ary: Exactly. People should give thought to new technologies that we use as a matter of course. In my view, technology is too often glamorised. I'd like us to pause and ask ourselves what we really need it for. Technology can do a lot of good, but it also has the potential to change our lives, our reality, our children who will be born in the future. It can change what it means to be human. With Bricolage we suggest that it could become possible to create life using technology. And we should reflect on whether we really want that.

Are your 'biological automatons' really alive?

Sebastian Diecke: They're made of living heart muscle cells that have grown in about 30 days. At this point they are mature and they don't develop any further. But in a nutrient solution they can last for longer. So in this sense, yes, they are alive.

Guy Ben-Ary: Our biological automatons don't just passively float around in a liquid. They pulsate and move independently. When people see something that moves by itself, they perceive it as being alive – even if they don't understand what it is. Visitors to the exhibition puzzle over the strange lifelike nature of Bricolage. Are they deep-sea creatures? Previously undiscovered life forms? Whatever they are, in the viewer's eyes they are alive.

Why do visitors have to look up? The incubator is suspended above their heads.

Guy Ben-Ary: Humans always assume that they are superior to other animals and other entities. We wanted to reverse this perception. Instead of standing above and looking down on the rest of the living world, with Bricolage people look up at our creation. We're playing with the idea that we don't know who we are and that we don't necessarily have to be better than the entities in the incubator.

Will Bricolage be exhibited in Berlin at some point – perhaps at the MDC?

Sebastian Diecke: We haven't given up hope and we are already considering how we could make the bio-automatons phosphoresce. But all plans are on hold at the moment due to COVID-19.

Interview by Jana Ehrhardt-Joswig

Further information

- The Well-Tempered Neuron

- Insight: Guy Ben-Ary, Nathan Thompson and Sebastian Diecke's 'Bricolage'

- SymbioticA