New muscles for the bladder

There are over 8000 known rare diseases, affecting more than 30 million people in Europe alone. Developing interventions for these mostly still untreatable diseases represents an important challenge for society and therefore to researchers. One such condition is epispadias, in which a developmental abnormality results in an abnormal position and splitting of the urethra and incomplete development of the urethral sphincter.

In Germany, only around seven boys and even fewer girls are born with this condition every year. It is associated with significant psychological stress, because although the externally visible malformation can be treated with surgery, in the case of the urethral sphincter this is unfortunately not so straightforward. "As a result, these children often suffer from lifelong incontinence, which causes considerable psychological stress for affected individuals and their families," says Professor Simone Spuler from the Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), a joint endeavor of Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and MDC. She is a specialist in stem cell and muscle research. "So we considered how we could use our expertise to help them."

The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) is funding the study with around €3.3 million. The Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité has supported the project with its Spark-BIH program on the way from the laboratory to the clinic with €1 million million.

Muscle stem cells build new sphincter muscle

The research team led by Simone Spuler had developed a method that allowed them to isolate regeneration-capable muscle stem cells from muscle tissue. "We take a biopsy, a tissue sample, from the thigh and from this we isolate muscle stem cells. We then propagate these cells many times over and inject them directly into the defective area of the urethral sphincter muscle." In rats, this caused a new sphincter muscle to develop, one that was actually functional. Because their altered immune system tolerated human cells, the same result was achieved with human muscle stem cells.

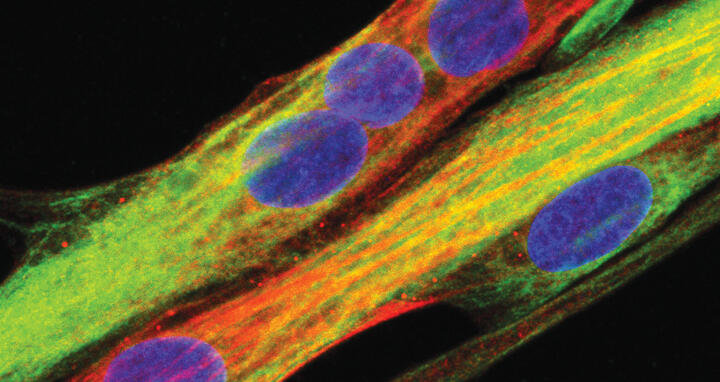

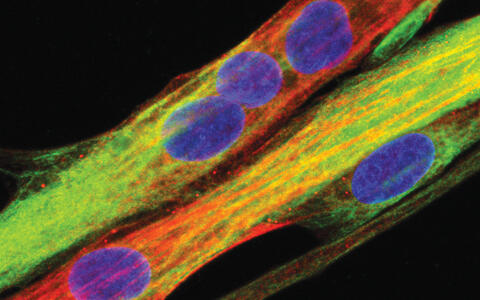

Human muscle cell as differentiated from muscle stem cells. (Blue: nucleus, green: desmin, red: myosin heavy chain).

But despite these encouraging results, we couldn't begin a clinical trial right away with real patients because there are strict regulations in place," the researcher explains. "In humans, we're only allowed to use cells produced in a pharmaceutical process in line with good manufacturing practice, or GMP. Setting up a process like this is very complex." Cells produced under GMP conditions are first used in an animal model for preclinical safety testing.

Support from the USA – and from BIH

Regulatory authorities – in Germany the Paul Ehrlich Institute – stipulate that only specially accredited laboratories are permitted to carry out the animal experiments for a clinical trial. These labs must comply with good laboratory practice (GLP). In the search for a GLP lab that also had microsurgery capabilities – allowing the muscle stem cells to be transferred into the rat sphincter – the researchers found what they were looking for in the USA. "There was a lab that met the criteria about 300 km east of Chicago, in the heart of Michigan," says Simone Spuler. "To explain to the team there exactly what we had in mind, we had to make several trips to the USA. The preparations, the necessary familiarisation and the conducting of experiments were all extremely time-consuming and expensive. Without the support of the BIH Spark programme, we could never have done it!"

BIH made €1 million available to Simone Spuler's muscle research team. "This is exactly in line with our purpose," explains Professor Christopher Baum, chairman of the Board of Directors of BIH and Chief Translational Research Officer of Charité. "We want to help researchers take their results from the lab to patients and in this way support clinical translation. This is how we turn research into health." Dr Tanja Rosenmund, the head of the BIH Spark programme, is also enthusiastic. "The reason the epispadias project is so exciting is that, if it succeeds, it will open up many other possibilities. Incontinence is a widespread problem, as is muscle weakness generally. So we hope that this funding will pave the way for many other studies."

Clinical trial with 21 boys

Now that the results in the USA have demonstrated that the transplanted muscle stem cells could prevent incontinence in rats and have also thoroughly confirmed the safety of the cell product, the clinical trial can go ahead. 21 boys aged between three and seventeen will receive treatment at the university hospitals in Ulm and Regensburg, where Professor Anne-Karoline Ebert and Professor Wolfgang Rösch lead centres for the bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex. The trial will take place on a placebo-controlled, randomised and double-blind basis. This means that a randomly selected five boys out of the group of 21 will be given a placebo (salt solution) instead of their own muscle stem cells. Neither the clinicians nor the patients will know which five these were until the end of the trial. "We have to do this to generate scientifically sound results," explains Spuler. "If the analysis of data shows that the children who received the cell injection are doing better than those who were given the placebo, those who didn't get the cell injection can of course be given it afterwards. This is possible because the isolated muscle stem cells can be stored without a problem by deep-freezing them."

The Federal Ministry of Education and Research was so impressed by the research proposal from Berlin that it made €3.3 million available to carry out the clinical trial. The first patient will be treated in a few months' time.

Text: Stefanie Seltmann, BIH

Download

Human muscle cell as differentiated from muscle stem cells (Blue: nucleus, green: desmin, red: myosin heavy chain).

Image: by courtesy from the American Society for Clinical Investigation; https://insight.jci.org

Dr. Stefanie Seltmann

Head of Communication & Marketing

Berlin Institute of Health at Charité (BIH)

+49-30-450-543019

stefanie.seltmann@bih-charite.de

Jutta Kramm

Head of Communications

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

+49-30-9406-2140

jutta.kramm@mdc-berlin.de oder presse@mdc-berlin.de

- About the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH)

-

-

The mission of the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) is medical translation: transferring biomedical research findings into novel approaches to personalized prediction, prevention, diagnostics and therapy and, conversely, using clinical observations to develop new research ideas. The aim is to deliver relevant medical benefits to patients and the population at large. The BIH is also committed to establishing a comprehensive translational ecosystem as translational research area at the Charité – one that places emphasis on a system-wide understanding of health and disease and that promotes change in the biomedical research culture. The BIH is funded 90 percent by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and 10 percent by the State of Berlin. The two founding institutions, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC), were independent member entities within the BIH until 2020. As of 2021, the BIH has been integrated into the Charité as the so-called third pillar; the MDC is privileged partner of the BIH.

- The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

-

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the MDC’s locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 60 countries analyze the human system – investigating the biological foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium in a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. The MDC therefore supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the MDC today employs 1,600 people and is funded 90 percent by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.