€700,000 boost for preeclampsia research

Two percent of all pregnant women in Europe develop preeclampsia – a condition that occurs after the 20th week of pregnancy and causes sudden high blood pressure and organ dysfunction. The elevated pressure in the blood vessels can damage both the mother’s blood vessels and those in the placenta. As a result, the unborn baby no longer receives sufficient nutrients and oxygen. This may lead to growth problems, long-term damage, or even miscarriage or stillbirth. In addition, the mother has a much higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease later in life.

Florian Herse

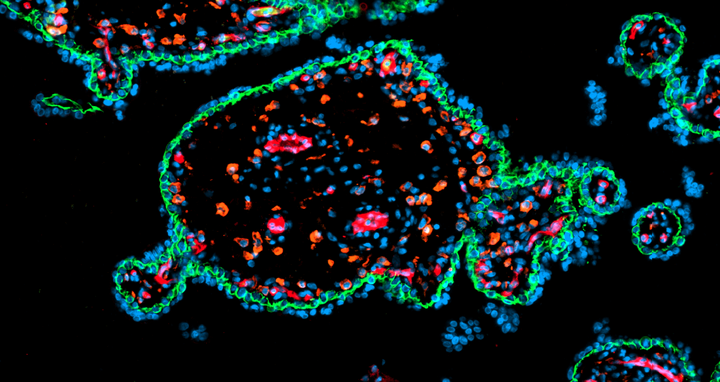

The causes and mechanisms of the disease are still not fully understood, but there is no doubt that the placenta – and its Hofbauer cells in particular – play a crucial role. Hofbauer cells are macrophages, a type of white blood cell that roams the body and kills pathogens. “Studies using animal models have shown that the clinical symptoms of preeclampsia disappear immediately after removal of the placenta,” explains Dr. Florian Herse. He is a researcher in Professors Dominik N. Müller’s and Ralf Dechend’s Hypertension-Mediated End-Organ Damage Lab at the Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), a joint institution of the Max Delbrück Center and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Together with Professor Martin Gauster of the Medical University of Graz, Herse plans to further investigate the development of these macrophages and their dysregulation in preeclampsia. The two researchers have been collaborating for ten years and will soon receive a D-A-CH grant for the second time. The funding process enables research proposals to be jointly submitted by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and its partner organizations, the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). Of the €700,000 in total funding, €372,000 will go to the Max Delbrück Center.

Shedding light on placenta impairment

Gauster and his team have developed a flow culture model for placental tissue that is capable of simulating the various states of health during pregnancy. In Berlin, Herse and Dr. Fabian Coscia’s lab are using single-cell sequencing and microscopy-guided proteomics to examine and compare the spatial and temporal dynamics of macrophage development in healthy and diseased placental tissue.

Hofbauer cells don’t circulate freely through the blood vessels but remain in the fetal area of the placenta, where they appear to prevent pathogens from passing from the mother’s blood to the unborn child. The number of these cells is reduced in pregnancies with severe preeclampsia. “We suspect that this changes the structure of the blood vessels and that of the tissues surrounding them, thereby impairing the function of the placenta,” says Herse. “So now we want to examine more closely how the macrophages and blood vessels interact.”

Text: Catarina Pietschmann

Further information

- Müller/Dechend Lab, Hypertension-caused End-Organ Damage

- Coscia Lab, Spatial Proteomics

- Research Team Gauster, Research Focus: Reproduction, Pregnancy and Regeneration

Contacts

PD Dr. Florian Herse

Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC) at Max Delbrück Center und Charité

+49 30 450 540 434

florian.herse@charite.de

Gunjan Sinha

Editor, Communications

Max Delbück Center

+49 30 9406-2118

gunjan.sinha@mdc-berlin.de oder presse@mdc-berlin.de

- Max Delbrück Center

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (Max Delbrück Center) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 70 countries study human biology – investigating the foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium of a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should be able to benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. This is why the Max Delbrück Center supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly-run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the Max Delbrück Center today employs 1,800 people and is 90 percent funded by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin. www.mdc-berlin.de