From basic researcher to cancer drug developer

“Retirement isn’t an option,” says Professor Claus Scheidereit. After 27 years, his Signal Transduction in Tumor Cells Lab at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) may be ceasing its work, but that doesn’t mean the end of his career as a scientist. For decades, he has been researching a family of transcription factors known collectively as NF-κB (pronounced NF-kappaB). This protein complex controls cellular processes during embryonic development, but also during the emergence of diseases – including various lymphomas. The results of Scheidereit’s basic research are now on the threshold of clinical application: the cell biologist wants to develop new cancer drugs.

Many tumors can be combated early on with chemotherapy and radiation therapy. “But tumor cells can evade these therapies by activating a signaling pathway that prevents them from dying,” Scheidereit explains. If the chemo or radiation causes double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA of the cancer cells, an enzyme called IκB kinase activates NF-κB, which in turn triggers a cell survival program.

Patent pending with the Technology Transfer Office

Claus Scheidereit really puts his heart and soul into his research.

Simply switching off this kinase, and thus NF-κB, is not an option: “NF-κB serves many physiological functions that also help to keep us healthy, so just blocking it would have serious side effects,” the researcher explains. But together with his team, Scheidereit has successfully identified two chemical substances that are able to selectively target only those IκB kinase/NF-κB signaling pathways in cells that have been damaged by chemo or radiation therapy, and prevent the repair program from being triggered. “My hope is that this finding will lead to a new class of drugs that enhance the effectiveness of chemo and radiation therapies,” says the researcher. One of the substances is already patented, and he has just submitted an “Invention Disclosure Form” for the second to the MDC’s Technology Transfer Office.

“Claus Scheidereit really puts his heart and soul into his research,” says Dr. Michael Hinz, a member of Scheidereit’s research group for several years and now Sustainability Officer at the MDC. Together, the scientists have published several joint papers. “I have fond memories of evenings together in his office, where we would go through manuscripts with a fine-tooth comb and debate every single word,” remembers Hinz. Scheidereit’s research group collaborated with MDC clinicians for many years. In 2005, he received the German Cancer Prize together with Professor Bernd Dörken from Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin for deciphering the molecular mechanisms of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

With age comes humility

Born in the German town of Schleswig in 1954, Claus Scheidereit did not originally have his sights set on science. His dream at the age of 17 was to become a pilot, but a slight color vision deficiency prevented this dream from becoming reality. His teacher thought this was a good thing, anyway: “Flying is no different to driving a bus, it’s just in the air,” he told the young man. So Scheidereit applied for a place at medical school instead, but decided while he was waiting that he actually wanted to study chemistry and biochemistry: “I was excited by the idea of getting to the bottom of things and being able to explain absolutely everything,” the 67-year-old recalls. “I’m a bit more humble about it today.” He says he was drawn to Philipps-Universität Marburg because of the fact it was a lively city with a very good department and lots of students.

It was his doctoral advisor, Professor Miguel Beato, who introduced Scheidereit to the world of molecular biology – a field of research that was only just emerging in the early 1980s. In his doctoral thesis, Scheidereit described that the receptor proteins for steroid hormones recognize specific DNA sequences in genes. His paper caused quite a stir among experts – and marked the beginning of his many years of research into gene regulation.

From Marburg to Manhattan

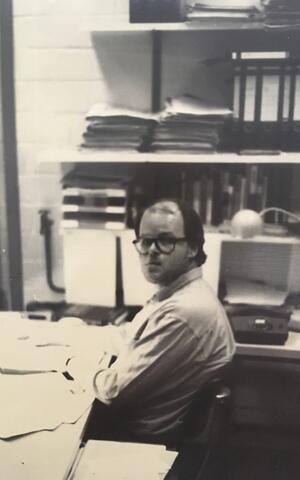

Claus Scheidereit in his lab in Harnackstraße 1990: This building of Max-Planck-Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin-Dahlem does not exist anymore.

With numerous publications and a doctorate under his belt, Scheidereit left the winding alleys and quaint half-timbered houses of Marburg behind and went to the Rockefeller University in New York. In Professor Robert G. Roeder’s lab, he researched how transcription is regulated in a gene-specific and cell type-specific manner. On the 15th floor of Rockefeller’s Tower Building, overlooking the East River, Scheidereit and his colleagues succeeded to identify the transcription factor NF-κB. He also discovered other factors that serve to ensure the blueprints contained within genes for the construction of proteins are executed. “Thousands of molecules are responsible for transmitting the relevant signals within and between the cells,” he says. “Many of the molecules and the underlying mechanisms are unknown. That’s why I find it so fascinating.”

In 1988, he was offered the opportunity to set up a research group at the Center for Molecular Neurobiology in Hamburg. He also had the option to go to the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg. But after three years in Manhattan, and because he and his wife are city dwellers through and through, he felt drawn to Berlin: “It was very important to us that we had a sushi bar just around the corner.” In Berlin, he started out heading a research group at the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Molecular Genetics before being appointed a lab head at the MDC in 1994. Scheidereit was coordinator of the MDC’s cancer research program from 2009 to 2020, as well as spokesperson for cancer research at the Helmholtz Association. Until 2021, he held seminars and lectures on the topic of biochemistry at Freie Universität Berlin as an adjunct professor.

Driving to work with Thomas Sommer

In 2013, Scheidereit launched the German-Israeli doctoral exchange program SignGene – Frontiers in Cell Signaling and Gene Regulation, where each thesis is the result of a collaboration between groups in Berlin and Israel. In addition to the MDC, initial project partners included Humboldt-Universität and Charité in Berlin, the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The idea for the project came about while Scheidereit was commuting to work with Professor Thomas Sommer, current interim Scientific Director of the MDC. For years, the two scientists shared their cars to and from the MDC every morning and evening.

So, our friendship began with a failure. And yet this did not damage it.

The two met in 1993 when Scheidereit was still at the MPI. Sommer and his research group were investigating how misfolded proteins are eliminated from cells by the ubiquitin-proteasome system – a process that should also play a role in the degradation of IκB proteins. Together, they wanted to find out whether this mechanism could be used to activate NF-κB. They started with their experiments – then a publication on exactly this process appeared in “Cell”. Another working group in the US came up with the same idea shortly before them. “So, our friendship began with a failure,” summarizes Sommer. “And yet this did not damage it.”

Team spirit is a key ingredient

Scheidereit believes that the success of a project hangs not only on scientific excellence – the most important factor in his view – but a good team spirit. This also applies to his working relationship with his secretary Daniela Keyner: “I am extremely grateful to her for always taking care of every thing with such care and dedication,” he enthuses. He gave the members of his research group a lot of freedom, but his door was always open when problems arose. “I’m not particularly fond of conflict,” he says. “I prefer to create a working environment where no conflicts arise in the first place.” Some 30 doctoral students as well as a number of postdocs started their scientific careers in Scheidereit’s lab. More than ten of his alumni are now leading their own research groups, and the others have also gone on to pursue interesting careers in science. He still keeps in touch with many of them: “They’re just all great people, which makes me so happy.”

Chemists are natural born cooks

Will Scheidereit’s wife be right in her prediction that he will continue to work until he drops? “I definitely want to be involved in the further development of these drugs,” he answers. “It would be a shame to stop now, knowing there are patients out there who could benefit from our work.” His wife is an art historian, and the couple often go to exhibitions together – as well as concerts, movies, and restaurants. “Claus Scheidereit is the best restaurant connoisseur in Berlin,” says Hinz. “I hope he writes a book about it one day.” But Scheidereit also enjoys being in the kitchen himself: “I love preparing food, it’s my favorite way to relax,” he says. “I started out as a chemist, after all – and all chemists can cook.”

Text: Jana Ehrhardt-Joswig