Stopping repair mechanisms in tumors

Rhabdomyosarcoma is not only one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in children and adolescents, but also a very severe form of cancer. Treatment for rhabdomyosarcoma, a malignant disease of the skeletal muscle, has remained virtually unchanged for decades despite having little success. “Only about 30 percent of the young people with a particularly aggressive form of the cancer – known as alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma – are alive five years after diagnosis,” says Heathcliff Dorado García.

The young Spaniard conducts research in Professor Anton Henssen’s Genomic Instability in Pediatric Cancer Lab at the Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), a joint institution of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin-based Max Delbrück Center. Henssen and Dorado García have made it their mission to finally develop a new and better treatment strategy for rhabdomyosarcoma.

The tumor disappeared completely

Elimusertib is highly effective in mice and is already being tested in initial clinical trials. Now we hope to achieve similarly good results in children and adolescents very soon.

Now, the two cancer researchers, along with other colleagues from Berlin and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, have reported important findings in the scientific journal “Nature Communications”. “We succeeded in making an alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma completely disappear in mice using certain therapeutic agents, including elimusertib,” says Dorado García, the paper’s first author. The team developed their mouse model from the tumor of a young patient who did not respond well to chemotherapy. So the tumors in the mice had the same molecular features as the tumor in the adolescent.

“Elimusertib is highly effective in mice and is already being tested in initial clinical trials,” says last author Henssen. “Now we hope to achieve similarly good results in children and adolescents very soon.” Henssen is not only a scientist, but also a pediatrician in Charité’s Department of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology, where he personally treats young cancer patients.

A changing number of chromosomes

The therapeutic agent elimusertib was developed by pharmaceutical company Bayer at its Berlin site, and is one of several ATR inhibitors that have been used in cancer treatment for some time now. In children, these have been trialed – although almost exclusively in vitro – in the treatment of neuroblastoma, some leukemias, and Ewing sarcoma, which primarily affects the bones. The drugs work by taking advantage of the many minor defects usually present in the genetic material of malignant cells: “ATR inhibitors block an enzyme that plays a significant role in repairing damaged DNA,” explains Dorado García. “As a result, the cell’s condition gets worse and worse until, at some point, the cell is no longer viable and it initiates programmed cell death – in other words, it commits suicide.”

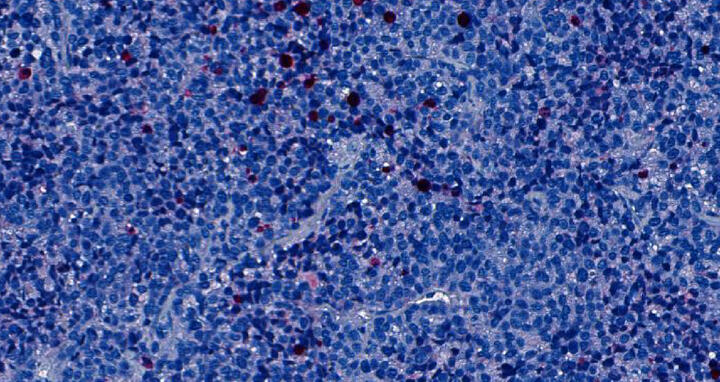

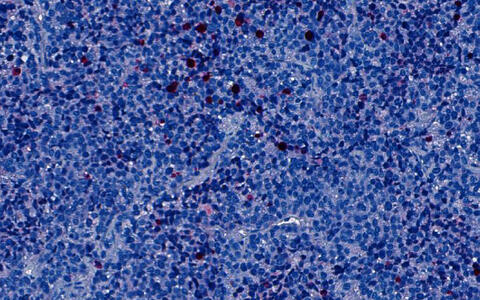

Tumor cells derived from a patient with alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma were implanted in a mouse. After the mouse was treated with an ATR inhibitor for two weeks, these cells were stained for a marker of cell death (in red /pink).

The experiments showed that cancer cells that produce a fusion protein called PAX3-FOXO1 were particularly sensitive to such inhibitors. Fusion proteins are formed by the co-expression of two genes that are adjacent to each other on a strand of DNA. “When they were treated with ATR inhibitors, these cancer cells became aneuploid – meaning their number of chromosomes changed,” explains Dorado García. And it is this, he goes on to say, that triggers cell suicide or apoptosis. “However, we were also able to show that PAX3-FOXO1 actually causes an increased amount of DNA damage in the cells,” says the researcher. “So cells with this protein are particularly dangerous, but they also react more sensitively to a disrupted DNA repair process than other cells.”

Combination therapies also possible

In addition, the doctoral student has already searched for the causes of possible resistance to ATR inhibitors – and has found them in the so-called FOS gene family. “FOS proteins are transcription factors that regulate the expression of other genes,” the researcher explains. “Overexpression of the FOS gene results in tumor cells no longer responding well to elimusertib and other ATR inhibitors.” The mechanism behind this is not yet fully understood, but Dorado García says further studies are in the pipeline.

He and Henssen are also currently examining combination treatments to prolong the effectiveness of the therapy – for example with the PARP inhibitor olaparib. This therapeutic agent uses a different mechanism to hinder the DNA repair of the tumor cells and is already approved for use with certain cancers, including breast and ovarian. Henssen assures us that a whole series of further preclinical data on this will be available soon.

First clinical trials underway

“Based on our findings, a trial with children and adolescents was launched in the United States in December 2021 to determine the safety and optimal dose of elimusertib,” the oncologist reports. The therapeutic agent is being tested for use in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, as well as in a number of other childhood cancers that have either not responded to standard therapy or that have come back.1 The study was initiated by Dr. Michael Ortiz from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, who was also involved in the current paper.

Researchers including Dr. Monika Scheer, a sarcoma expert at Charité, are also preparing to commence clinical trials in Berlin – particularly on combination therapies. “And finally,” Henssen says, “we would like to identify other factors in the near future that make pediatric tumors more sensitive to ATR inhibitors and similar agents.” He is hopeful that drugs that interfere with the repair of damaged DNA in malignant cells could also help children suffering from other types of cancer that are even more common and similarly difficult to treat.

Text: Anke Brodmerkel

Further information

Literature

Heathcliff Dorado García et al (2022): „Therapeutic targeting of ATR in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma“. Nature Communications, DOI: s41467-022-32023-7