A glitch in the heart’s protein factory

An abnormal increase in heart muscle mass is considered the most common cause of sudden cardiac death. Now, a team of scientists led by Professor Norbert Hübner, head of the Genetics and Genomics of Cardiovascular Diseases Lab at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) in Berlin, has figured out what’s behind this hypertrophy. Another MDC research group – the “Non-coding RNAs and Mechanisms of Cytoplasmic Gene Regulation Lab”, led by Dr. Marina Chekulaeva – was also involved in the study.

The scientists have uncovered a complex molecular mechanism that interferes with the overall protein production in the ribosomes of heart cells. As a result, the heart does not get the proteins it needs. This production defect, in turn, promotes abnormal growth of heart muscle cells. The study, which involved 19 researchers from six countries, has been published in the journal “Genome Biology”.

The entire protein production is impaired

“We wanted to find out how natural genetic variation, which is present in every living being, can contribute to the development of complex diseases,” says Dr. Sebastiaan van Heesch, who is the study’s co-last author along with Hübner. Until June 2020 the Dutchman was a postdoc in Hübner’s lab at the MDC. He has since set up his own lab back in his home country, at the Prinses Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology in Utrecht.

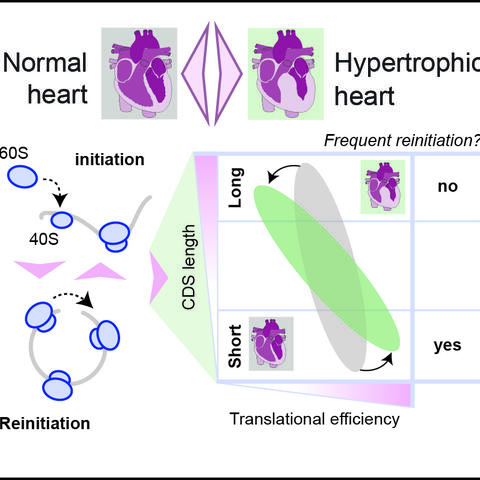

“It was already known that differences in the genome can influence whether and how genes are read in the cell nucleus,” says van Heesch. This process, known as transcription, is the first step in protein production. Scientists were also aware that certain changes in the DNA can lead to the production of defective heart proteins. “But the fact that genetic variants can affect the heart’s entire protein production by interfering with cellular protein factories – the ribosomes – was new and rather surprising,” says van Heesch.

Particularly devastating for long proteins

“In our study, we worked with a group of rats for which we know all the genetic variants and we also know that about half of the animals in this panel of hybrid strains develop heart disease,” reports Dr. Jorge Ruiz-Orera, a scientist from the same group. Ruiz-Orera is co-lead author of the study along with Dr. Franziska Witte, who was a doctoral student in Hübner’s lab during the first years of the study and now works at the Berlin-based research firm Nuvisan.

What is especially remarkable is that similar genetic variants also have the same effects on protein synthesis in other species – for example, in mice, humans, and even in unicellular organisms like yeast.

“To find out more about the reasons behind the rats’ cardiac hypertrophy, we looked for a link between the animals’ DNA and the function of their ribosomes. That’s where translation, or protein production, takes place,” says Ruiz-Orera. The researchers also examined whether errors in protein production could be related to the known enlargement of the hearts.

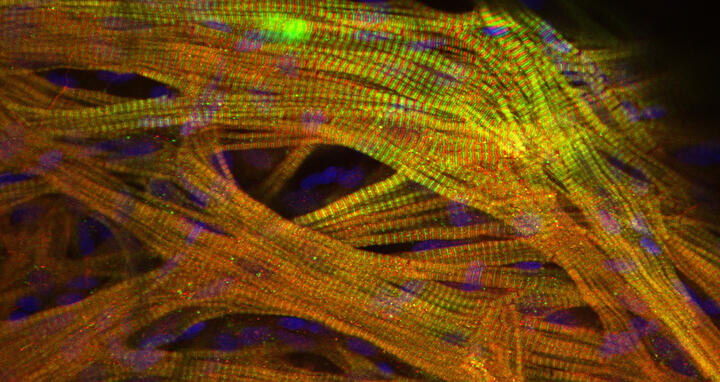

In these investigations, the team came across an altered region in the rats’ genome that results in a defect in overall protein synthesis. However, this defect affects long and short proteins differently. “The effect is not as devastating in short proteins,” explains Ruiz-Orera. “But long proteins, such as the important muscle protein titin, are produced much less efficiently. We were able to show that this has a negative effect on the assembly of sarcomeres, the smallest functional unit of the muscle fiber.” Ultimately, this defect leads to a thickening of the heart chambers and heart failure.

Similar effects even seen in yeast cells

“What is especially remarkable is that similar genetic variants also have the same effects on protein synthesis in other species – for example, in mice, humans, and even in unicellular organisms like yeast,” reports Hübner. This shows, he says, just how widespread the genetically determined defect is in the cellular protein factories, how little it has changed over the course of evolution, and how important a role it plays in the development of complex diseases that also affect humans.

“The mechanism we uncovered may explain why some people are genetically predisposed to develop cardiac hypertrophy,” says Hübner. “In addition, our work lays the groundwork for future studies on the genetic predisposition to complex diseases that can affect organs other than the heart.”

Text: Anke Brodmerkel

Further information

- Van Heesch Lab at the Prinses Máxima Centrum für Pädiatrische Onkologie in Utrecht

- Unknown mini-proteins in the heart

Literature

Franziska Witte, Jorge Ruiz-Orera et al. (2021): “A trans locus causes a ribosomopathy in hypertrophic hearts that affects mRNA translation in a protein length-dependent fashion”. Genome Biology, DOI: 10.1186/s13059-021-02397-w

Contact

Jana Schlütter

Editor, Communications Department

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

+49 30 9406 2121

jana.schluetter@mdc-berlin.de or presse@mdc-berlin.de

- Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the MDC’s locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 60 countries analyze the human system – investigating the biological foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium in a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. The MDC therefore supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the MDC today employs 1,600 people and is funded 90 percent by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.