Inborn immunodeficiency discovered – and explained

Joint press release with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

In a study of seven children with profound immunodeficiency, an international consortium of researchers has discovered a T95R mutation in the gene for interferon regulatory factor 4. IRF4 is a transcription factor that controls proteins, which means it regulates how much messenger RNA a cell produces. But it also plays a key role in the development and activation of immune cells. The seven patients came from six unrelated families living on four different continents. The research team, which includes the group led by Prof. Stephan Mathas and Dr. Martin Janz at the ECRC (Experimental and Clinical Research Center, a joint institution of the Max Delbrück Center and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin), were also able to identify how the mutation affects the immune system. A previously undescribed mechanism causes an inborn combined immunodeficiency. The consortium has now published its findings in Science Immunology.

In addition to the two German research groups – from Charité/Max Delbrück Center and the University of Ulm – the consortium includes researchers from children’s hospitals and universities in Canberra (Australia), Shanghai (China), Vancouver (Canada), Paris (France) and Nashville (USA), as well as from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda (USA).

Susceptible to upper respiratory infections

Immunodeficient children frequently contract infections of the upper airways.

Inborn immunodeficiencies are rare and often vary in severity. “Immunodeficient children frequently contract infections of the upper airways,” says Mathas, who specializes in the molecular biology of transcription factors and leads the Biology of Malignant Lymphomas Lab at the ECRC. The illnesses are often caused by Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, or Pneumocystis jirovecii, a pathogen that causes pneumonia. These are all infections that physicians regularly see in other patients with immunodeficiencies.

The seven patients in this study also suffer from these infections. When the researchers delved deeper, they found that the children’s immune systems shared some similarities: “All the children have too few antibodies in their blood and very few B cells, which normally produce the antibodies. They also have fewer T cells than healthy individuals, and the T cells they do have function less well,” says Mathas. Alongside B cells and antibodies, T cells are an important pillar of the immune system.

In many children who are born with an immunodeficiency, the cause of the condition is unknown. Today, though, genome sequencing can help shed light on it. This was how the study’s authors discovered the T95R mutation in IRF4. By collaborating closely in international networks, the researchers traced the genetic cause of the disease in these children from unrelated families to the same point mutation. This makes them the index patients – the first described cases – for this deficiency. The consortium was also able to produce the same syndrome in mice by specifically mutating the Irf4 gene. This allowed the researchers to gain a more detailed understanding of the errors of immunity caused by IRF4.

Spontaneous mutation in the germline

The T95R mutation is only ever found on one of the two copies of the genome. And although the patients also always produce healthy IRF4, they all develop the immunodeficiency. “The biology of the mutation effectively beats the biology of the healthy form,” says Mathas. Genome analysis of the families revealed that the index patients didn’t inherit the mutation from their parents. Rather, it occurred spontaneously (de novo) in the germline or during early embryonic development.

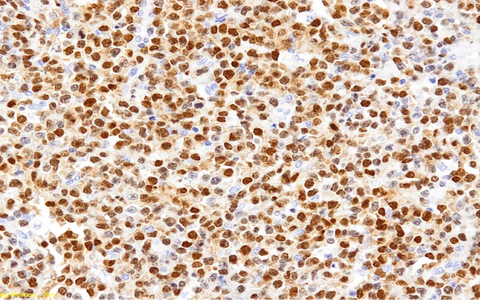

Analysis of IRF4 (colored brown) in a form of lymphoma.

The mutation in transcription factor IRF4 occurs at the precise location where the protein binds to DNA. Usually, the amino acid threonine (T) is found here, but in the mutation it is replaced by arginine. “In conjunction with other factors, the mutation changes IRF4’s affinity for DNA,” says Mathas. This means that, as well as binding to known DNA binding sites with varying degrees of strength depending on the context, the mutated IRF4 protein also binds to parts of the genome that it shouldn’t be involved in at all – sites that the normal variant of the protein (the wild type) would never bind to. Bioinformatics analyses allowed the researchers to identify these new binding sites. They describe the mutation in their paper as “multimorphic” because as well as blocking certain genes, it also activates others – and even new ones.

More genes for diagnosing deficiencies

Depending on the type and severity of an inborn immunodeficiency, patients might undergo stem cell transplants or receive regular antibody injections throughout their lives. “Now our study suggests that it would be possible to change a mutated transcription factor’s binding sites without affecting the healthy variant,” says Mathas.

The T95R mutation in IRF4 will now be added to the catalogue of genes used to diagnose inborn immunodeficiency. Interestingly, IRF4 also plays an important role in the development of certain types of blood cancer, which Mathas’s lab is also investigating.

Text: Catarina Pietschmann

Further information

Literatur

IRF4 International Consortium (2023): „A multimorphic mutation in IRF4 causes human autosomal dominant combined immunodeficiency“. Science Immunology, DOI:10.1126/sciimmunol.ade7953

Downloads

Analysis of IRF4 (colored brown) in a form of lymphoma.

Credit: Prof. I. Anagnostopoulos, Pathologie Uniklinik Würzburg

Contacts

Prof. Stephan Mathas

Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC) of the Max Delbrück Center and Charité

+49 30 450 553112 (Department of Hematology, Oncology and Tumor Immunology, Campus Charité Mitte)

stephan.mathas@charite.de

Christina Anders

Editor, Communications Department

Max Delbrück Center

+49 30 9406-2118

christina.anders@mdc-berlin.de oder presse@mdc-berlin.de

- Max Delbrück Center

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (Max Delbrück Center) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 70 countries study human biology – investigating the foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium of a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should be able to benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. This is why the Max Delbrück Center supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly-run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the Max Delbrück Center today employs 1,800 people and is 90 percent funded by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.