📺 Dauntless, visionary, inspiring – Detlev Ganten turns 80

"Akademie der Wissenschaften" board

The day of September 2, 1991, began like any other on the Buch research campus. At the former central institutes of the GDR Academy of Sciences, no one suspected that in Bonn, at the Federal Research Ministry, a new director had just been appointed. He would come to Berlin that very afternoon – with the mission of creating something totally new out of the three Academy institutes and their some 2,000 employees. “It was important to me to immediately introduce myself in person. I didn’t want my people to read about it in the newspaper,” Detlev Ganten would later say. Recalling the tense atmosphere of his first meeting, he noted, “I was an unknown West German with plans for change. Of course people were skeptical.”

Jubilee Film - 100 Years Campus Berlin-Buch

A man of determination and vision

We owe him a very great deal, and we’re pleased that he is still active at the MDC.

Soon enough, skepticism gave way to optimism. Over the years, Berlin-Buch became a world-renowned biomedical research campus with a focus on patients and its own business park. At its heart: the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC). The fact that things turned out this way and not otherwise is all thanks to Detlev Ganten. Berlin-Buch is his masterpiece. “He was a trailblazer, and he proceeded with great prudence.” Such is the assessment of his former boss, former Federal Research Minister Heinz Riesenhuber. Thomas Sommer, interim Scientific Director of the MDC and a long-time associate, adds, “We owe him a very great deal, and we’re pleased that he is still active at the MDC, as a source of advice to many people and a font of ideas for his friends.”

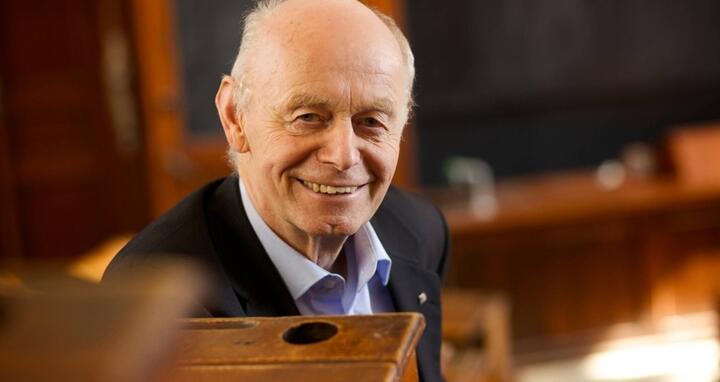

Both men praise Ganten’s ability to reach out to people and listen to them, as well as his dauntlessness, tenacity, determination, and vision – qualities that would open many doors to him at Buch and beyond. They were already on display in the key scene in 1991, when a fifty-year-old pharmacology professor from Heidelberg introduced himself in Berlin-Buch as the new founding director. “I was still a young man then,” Ganten recently noted with an impish grin. He turned eighty on March 28, 2021. A bust was unveiled in his honor on the Campus Buch.

Detlev Ganten is a child of the Second World War. He was born in Lüneburg in 1941 and grew up near Bremerhaven with his four siblings. “I experienced the sufferings of the final period of the war and the following years. I saw a lot of misery,” he says in an interview available on this website, part of a series of conversations with founding figures of the MDC. His parents were very conservative. His father was a member of the Nazi Party. This would later lead to intense conflicts within the family, Ganten relates, but it also helped him to better understand how people can get ensnared in political systems.

Today I’m overjoyed that Ganten got the job. It was tough at first, but he created a magnificent institution.

Expert on high blood pressure

After graduating from high school, the young Ganten initially trained as an agricultural worker. “Country life was a big influence on me, with the constant presence of animals,” he later reported, still cognizant of the difficulties this kind of work entailed. His interest in nature and a desire to do good for humanity ultimately propelled him to study medicine at the universities of Würzburg, Montpellier, and Tübingen – including a semester working in the French hospital in Marrakesh. After completing his M.D., his love of the Francophone world took him to McGill University in Montreal, Canada, where he conducted research from 1969 to 1973 and earned a Ph.D. This was followed by a lengthy stint at the Institute of Pharmacology at the University of Heidelberg (1973–1991). Ganten became a professor there in 1975, specializing in research on high blood pressure. His award-winning studies on the hormonal regulation of blood pressure, focusing in particular on the renin-angiotensin system, was in part responsible for making high blood pressure the manageable condition it is today.

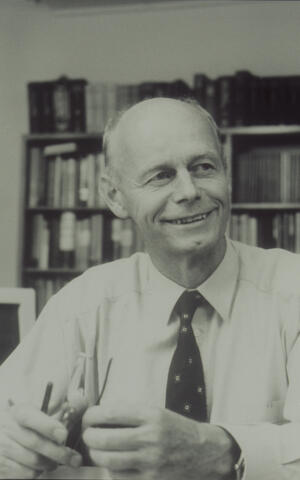

Detlev Ganten on the fall of the Berlin Wall

Then he was offered the position in Berlin. The advice to appoint Detlev Ganten came from “the orbit of the Council of Science and Humanities,” Heinz Riesenhuber recalls. That powerful body had reviewed the state of East German scientific research right after reunification, introducing many efforts to restructure it and install new people. “The task was difficult,” recalls the long-serving Federal Research Minister known for his bowtie. “We wanted to inculcate liberal science and buttress the willingness to engage in open-minded competition.” The two men met a few times, after which Riesenhuber asked Ganten to set up a new kind of research institute in Berlin-Buch. In Riesenhuber’s opinion, “he succeeded thanks to his great organizational know-how and passion for science.”

Crossing the border from the West

It was a giant step for the professor from Heidelberg – from the familiar, tidy town on the Neckar River to the foreign world of the “wild East.” He was accompanied by his wife Ursula Ganten, a physician, and the couple moved into an austere two-room apartment in the Buch guest house. Their two sons were already grown and remained in West Germany. “We were the first West Germans. We didn’t know anyone, and socially it was a risky situation too,” recalls Detlev Ganten in his MDC video interview. The Gantens quickly built a house – right next to the campus, although technically in Brandenburg. The founding director’s commute was a five-minute walk, leading over a narrow board and through a hole in the fence. “This total immersion in my new situation was incredibly important, also from a psychological point of view,” says Ganten. As a West German manager in the East, he consciously decided against adopting the standard Tuesday-Wednesday-Thursday commuter rhythm. Instead, he and his wife put all their eggs in this one basket.

Detlev Ganten about his move from Heidelberg to Berlin

Opening ceremony with Germanys Federal President

It sent a strong signal, but there was a great deal of mistrust. “I had hoped that my friend Heinz Bielka would get the job. At the time he was deputy director of the Central Institute for Molecular Biology and politically uncompromised,” recalls Erhard Geißler, professor of genetics and a fixture of the Buch community. “But now a professor from Heidelberg was thrown in our face.” What to do? Detlev Ganten went about things in his trademark way. He had an open-door policy at his office, inviting everyone to air their concerns freely. “I was practically talking to people around the clock. In the evening we’d drink Flensburg beer and red wine together, which helped us get to know each other better.”

Federal Research Minister Heinz Riesenhuber, Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker and Founding Director Prof. Dr. Detlev Ganten (from left) at the opening ceremony of the MDC in 1992.

Ganten remarked in a recent interview that in the beginning he had no idea how things would go, and that he was dependent on help from others. “I told them so openly, and that really got the energy flowing. Everyone wanted to contribute to our success, even the administrators, the usual bêtes noires of scientists.”

On January 1, 1992, only three months after Ganten’s arrival at the campus, the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) was founded. The opening ceremony was attended by then Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker. The center was named in honor of the Nobel laureate and unconventional pioneer of modern genetics Max Delbrück. Its name also invoked the location’s venerable history, which goes all the way back to days of the Kaiser. In his own typical way, Ganten capitalized on the unifying power of common traditions. On this basis, the MDC went on to become a trailblazing research institution – with flat hierarchies and youthful, independent research groups.

Opening of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine 1992. Front row, from left to right: Research Minister Dr. Heinz Riesenhuber, President Dr. Richard von Weizsäcker, Prof. Dr. Detlev Ganten, Dr. Ursula Ganten, Dr. Erwin Jost, Health Senator Dr. Peter Luther, Prof. Dr. Harald Zurhausen, Director of the Deutsche Krebsforschungszentrum

Competition between East and West, and a great deal of freedom

The first junior group leader at the MDC was Helmut Kettenmann. “You have to see this place,” his former colleague Ganten said to him on the telephone, luring him from Heidelberg to Berlin. “There were a handful of us young scientists from West Germany. We lived together in the guest house. There was always a line for the one telephone that could make calls to the West,” recalls Kettenmann, who would go on to achieve great fame as a neuroscientist at the MDC. Thinking back on those early years, he remembers “social stress” stemming from bitter competition, as more than two thousand scientists were fighting for 350 positions – that’s all the MDC’s budget could support at the beginning. With the assistance of federal programs, EU funds, and spin-off programs, the new director was able to provide many former employees with financial support, at least for a while. “No one could have done a better job,” Kettenmann is convinced. Even the initially reserved Erhard Geißler says, “Today I’m overjoyed that Ganten got the job. It was tough at first, but he created a magnificent institution.”

Prof. Dr. Detlev Ganten, founding director of the MDC, at his office.

Detlev Ganten was head of the MDC for twelve years, until 2004. In that period, things got better and better. From a scientific point of view it was paradise on Earth, says Thomas Sommer, who came to Buch as a junior group leader in 1993. “We had unimaginable freedom.” That drew even more young talent and leading scientists from Germany and abroad to the Buch campus. Beautiful new buildings with laboratories and offices were built, a sculpture park was opened, clinical collaborations were expanded, and the adjoining biotechnology park soon had to be enlarged. This was also welcome news politically in Berlin, and it led to good relationships that Ganten attentively fostered – despite a jam-packed schedule. Indeed, he accrued many duties during his years in Buch: a seat on the German Council of Science and Humanities and the German Ethics Council, chairman of the Helmholtz Association, and president of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians – to name only a few of his positions. How such a busy individual also managed to produce a scientific encyclopedia (Leben, Natur, Wissenschaft – Alles, was man wissen muss, 2003, 600 pages) is a mystery.

Charité and the World Health Summit

The basic research conducted at the MDC is intended to benefit sick people as quickly as possible. From the very beginning it has therefore enjoyed a close relationship with one of the largest university hospitals in Europe, Charité. In 2003, the Berlin Senate decided to fuse the previously competing hospitals of the Free and Humboldt Universities as “Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.” The task for implementing this resolution was soon entrusted to Detlev Ganten. “I fought like mad to keep all three locations,” the former chairman said in a later interview. And he was successful, also managing from the start to instill a sense of community. Unfortunately, the head of Charité could not withstand the increasing pressure to cut costs and all the consequences this entailed. In September 2008, Ganten handed over his office to neurologist and former chairman of the German Council of Science and Humanities Karl-Max Einhäupl.

Shortly thereafter Detlev Ganten began his third career. “He walked into my office and suggested founding a World Health Summit at Charité,” reports Einhäupl. The latter was unimpressed, indeed unconvinced it would be of any use. But Ganten was undaunted. “The next time he came,” Einhäupl recalls, “he had gotten Chancellor Merkel and then French President Nicolas Sarkozy to sponsor the idea, and he was so enthusiastic that I couldn’t say no anymore.”

Interview with Detlev Ganten and his role as President of the World Health Summit (2009 - 2020)

The first World Health Summit (WHS) took place in 2009, as one of the highlights of Charité’s 300-year anniversary – with Detlev Ganten as founding president. About 700 experts in the fields of medicine, economics, politics, and civil society came from many countries to discuss questions of global healthcare and make recommendations. Since then, the WHS has met annually in October in Berlin. Around 2,500 international specialists now participate at the summit. There are also regional meetings all over the world. The summit’s supporters include the European Commission and the WHO.

Honoring Helmholtz and Virchow

“Today the World Health Summit is one of the most important meetings of international specialists,” says Ilona Kickbusch, professor of global health in Geneva. In her view, Germany had never been a big actor on this stage before. “That has fundamentally changed. Now ministers from all over the world feel offended if they are not invited,” reports Kickbusch, who has attended every year since 2009 and has helped to develop the event’s format. The German government has been a major player in the field of global health for several years now, and its engagement has been reinforced and highlighted by the WHS, says Kickbusch. “It is a very strong organization that Detlev Ganten is now handing over to the new head of Charité.”

In his eightieth year, the tireless researcher, scientific manager, and humanitarian has again decided to start something new. He is involved in the Berlin Science Year 2021. Among other things, he is giving readings from his new popular science book Die Idee des Humanen, which focuses on Hermann von Helmholtz and Rudolf Virchow. Will he even have time for a birthday party? Perhaps later in the year? This is how Detlev Ganten’s recently responded to that question: “We always have time for what’s important to us. And celebrating with friends, whatever the occasion, has always been important in my life.”

Detlev Ganten with Delbrück's children Jonathan Delbrück and Nicola Salmon.

Text: Lilo Berg