Preeclampsia: What tiny veins can tell us

Last year, about 54,000 pregnant women in Germany developed preeclampsia – a condition that occurs after the 20th week of pregnancy and causes sudden high blood pressure and organ dysfunction, usually in the kidneys, liver or brain. If the placenta is damaged by not receiving enough blood, the unborn baby may not receive sufficient nutrients and oxygen. This can cause growth problems, long-term damage, or even miscarriage or stillbirth.

Award for the best abstract

Dr. Kristin Kräker

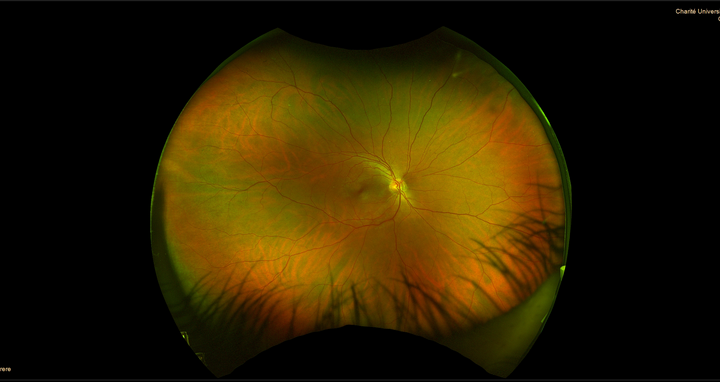

In most cases, the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia go away after delivery. Yet studies show that patients have up to a fourfold increased risk of contracting cardiovascular disease later in life. Dr. Kristin Kräker, who is affiliated with both the Hypertension-Mediated End-Organ Damage Lab of Prof. Dominik Müller and Prof. Ralf Dechend and the Clinical Research Unit of the Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), wants to find out why. The ECRC is a joint institution of the Max Delbrück Center and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The scientist also seeks to develop diagnostic techniques and identify potential biomarkers that can be used to identify at an early stage those women most at risk. Her idea: The tiny veins of the retina may provide information about the condition of the maternal blood vessels after delivery, and thus about the risk of future cardiovascular disease. She won the Paul Dudley White International Scholar Award of the American Heart Association for her presentation of this approach at this year’s Hypertension Scientific Sessions. This award recognizes the team of authors with the highest-ranked scientific abstract from each participating country at the AHA scientific meeting. In a project funded by the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), Kräker used genetically modified rats to investigate whether and how blood vessels change at the end of pregnancy and after delivery. Working with scientists from the Max Delbrück Center’s Animal Phenotyping Platform, she developed a method that can visualize vessels down to a diameter of four micrometers in various organs. For comparison, a human hair measures about 50 to 100 micrometers in diameter. This novel technique enabled her to discover that a possible cause for the increased cardiovascular risk might be that there are fewer small vessels that supply the heart after a preeclamptic pregnancy. She also found out that these microvessels become more numerous in the eyes of formerly preeclamptic rats.

Seeking study participants

To confirm her findings, Kräker is now working under the auspices of the CARPE Study to determine whether imaging of the blood vessels on the eye’s back wall or specific markers for vascular stiffness can provide an early indication of increased cardiovascular risk. She is collaborating with Prof. Jeanette Schulz-Menger, who heads Charité’s Outpatient Clinic for Cardiology on Campus Berlin-Buch, and with Dr. Hanna Zimmermann, who leads the ECRC’s Interdisciplinary Retina Research Lab. Participants are still being sought for the study, which is open to women who had a preeclamptic pregnancy. The study is also recruiting healthy women for the control group who gave birth to their first child within the previous 5 to 10 years. In addition to an expense allowance, participants will receive an MRI scan of their heart, comprehensive information on body composition, blood pressure, and vascular stiffness, as well as information on visual acuity and the condition of retinal vessels. If you are interested in taking part in the study, please contact us by phone at (030) 450 540 565 or by email at carpe@charite.de.

Text: Jana Ehrhardt-Joswig

Further information

- A potential agent for treating peeclampsia – Press release of the Max Delbrück Center