3D maps of diseased tissues at subcellular precision

Researchers in the Systems Biology Lab of Professor Nikolaus Rajewsky have developed a spatial transcriptomics platform, called Open-ST, that enables scientists to reconstruct gene expression in cells within a tissue in three dimensions. The platform produces these maps with such high resolution, that researchers are able to see molecular and (sub)cellular structures that are often lost in traditional 2D representations. The paper was published in the journal “Cell.”

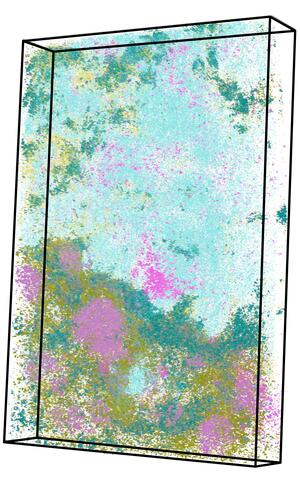

3D virtual tissue block. Colors indicate expression of select genes

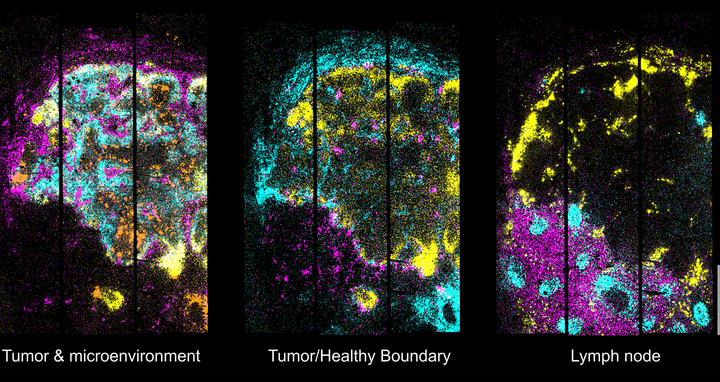

In tissues from the brains of mice, Open-ST was able to reconstruct cell types at subcellular resolution. In tumor tissue and a healthy and metastatic lymph node from a patient with head and neck cancer, the platform captured the diversity of immune, stromal, and tumor cell populations. It also showed that these cell populations were organized around communication hotspots within the primary tumor, but this organization was disrupted in the metastasis.

Such insights can help researchers understand how cancer cells interact with their surroundings and, potentially begin exploring how they evade the immune system. Data can also be used to predict potential drug targets for individual patients. The platform is not restricted to cancer and can be used to study any type of tissue and organism.

“We think these types of technologies will help researchers discover drug targets and new therapies,” says Dr. Nikos Karaiskos, a senior scientist in the Rajewsky lab at the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology of the Max Delbrück Center (MDC-BIMSB) and a corresponding author on the paper.

Unveiling the spatial complexity of tissues

Transcriptomics is the study of gene expression in a cell or a population of cells, but it usually does not include spatial information. Spatial transcriptomics, however, measures RNA expression in space, within a given tissue sample. Open-ST offers a cost-effective, high-resolution, easy-to-use method that captures both tissue morphology and spatial transcriptomics of a tissue section. Serial 2D maps can be aligned, reconstructing the tissue as 3D “virtual tissue blocks.”

“Understanding the spatial relationships among cells in diseased tissues is crucial for deciphering the complex interactions that drive disease progression,” says Rajewsky, who is also Director of MDC-BIMSB. “Open-ST data allow to systematically screen cell-cell interactions to discover mechanisms of health and disease and potential ways to reprogram tissues.”

We have achieved a completely different level of precision

Open-ST images from cancer tissues also highlighted potential biomarkers at the 3D tumor/lymph node boundary that might serve as new drug targets. “These structures were not visible in 2D analyses and could only be seen in such an unbiased reconstruction of the tissue in 3D,” says Daniel León-Periñán, co-first author on the paper.

“We have achieved a completely different level of precision,” adds Rajewsky. “One can virtually navigate to any location in the 3D reconstruction to identify molecular mechanisms in individual cells, or the boundary between healthy and cancerous cells, for example, which is crucial for understanding how to target disease.”

Cost-effective and accessible technology

One significant advantage of Open-ST is cost. Commercially available spatial transcriptomics tools can be prohibitively expensive. Open-ST, however, uses only standard lab equipment and captures RNA efficiently, reducing costs significantly. Lower costs also mean that researchers can scale up their studies to include large sample sizes, to study patient cohorts, for example.

2D map of gene expression in the metastatic lymph node

The researchers have made the entire experimental and computational workflow freely available to enable widespread use. Importantly, the platform is modular, says León-Periñán, so Open-ST can be adapted to suit specific needs. “All the tools are flexible enough that anything can be tweaked or changed.”

“A key goal was to create a method that is not only powerful but also accessible,” says Marie Schott, a technician in the Rajewsky lab and co-first author on the paper. “By reducing the cost and complexity, we hope to democratize the technology and accelerate discovery.”

Text: Gunjan Sinha

Further information

Literature

Marie Schott, Daniel León-Periñán, Elena Splendiani et.al (2024): „Open-ST: High-resolution spatial transcriptomics in 3D.“ Cell, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.055.

Photos for download

3D virtual tissue block. Colors indicate expression of select genes. Photo: AG N. Rajewsky, Max Delbrück Center

2D map of gene expression in the metastatic lymph node. Photo: AG N. Rajewsky, Max Delbrück Center

Contacts

Prof. Dr. Nikolaus Rajewsky

Head of the Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements Lab

Director of the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology of the Max Delbrück Center (MDC-BIMSB)

Office of the Rajewsky Lab

Alexandra Tschernycheff

+49 30 9406 2999

+49 30 9406 3068

tschernycheff@mdc-berlin.de

Dr. Nikos Karaiskos

Senior Scientist in the Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements Lab

Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology of the Max Delbrück Center (MDC-BIMSB)

Nikolaos.Karaiskos@mdc-berlin.de

Gunjan Sinha

Editor, Communications

Max Delbrück Center

+49 30 9406-2118

Gunjan.Sinha@mdc-berlin.de or presse@mdc-berlin.de

- Max Delbrück Center

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (Max Delbrück Center) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 70 countries study human biology – investigating the foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium of a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should be able to benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. This is why the Max Delbrück Center supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly-run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the Max Delbrück Center today employs 1,800 people and is 90 percent funded by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.