The tricks of lymphomas

Immunotherapies have become an indispensable part of modern cancer treatment. Antibody therapies are particularly effective against cancers like Hodgkin’s disease, a type of blood cancer that attacks the lymphatic system. When it comes to aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, however, comparable approaches that employ various strategies to incite the immune system to attack the tumor cells typically end in failure.

Lymph node architecture is disrupted

Our study now provides deeper insights into the methods tumor cells use to create protective niches in lymph nodes.

The probable reason for this failure has now been uncovered by a team led by Dr. Armin Rehm, head of the Translational Tumor Immunology Lab at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) in Berlin. “In experiments with mice and human tumor tissue, we were able to show that the cancer cells disrupt the delicate architecture of the lymph nodes,” explains Dr. Lutz Menzel, first author of the “Cell Reports” paper and a researcher in Rehm’s lab.

This ultimately leads to a group of large blood vessels – the high endothelial venules – losing one of their most important functions. “Without these intact vessels, immune cells cannot migrate into the lymph nodes on their patrols to track down tumor cells,” explains Menzel. Several research groups at the MDC were involved in the German Cancer Aid-funded study, including the Microenvironmental Regulation in Autoimmunity and Cancer Lab led by Dr. Uta Höpken.

Identical findings in mice and humans

“We knew from a previous study that aggressive lymphomas, such as diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, stimulate the growth of small capillary-like vessels in the lymph nodes,” says Rehm. In this way the tumor cells ensure that they are optimally supplied with nutrients during their rapid growth. “At the same time, microscopic examinations showed us that there were very few blood vessels with larger diameters in the affected lymph nodes,” reports Rehm, adding that the findings in mice were identical to those in humans with aggressive lymphomas.

In the current study, the researchers first used mice to investigate how the loss of high endothelial venules occurs, a situation that allows lymphomas to evade attack by the cellular immune system. “We discovered a complex cascade of changes which include the scaffold structures in the lymph nodes being disrupted,” says Menzel. “Such disruption causes changes in the pressure and volume ratios, both of which influence gene expression.”

This, he says, eventually leads to high endothelial venules being transformed into completely normal blood vessels, thus cutting off the immune cells’ access to the cancer cells. The team was then able to confirm these observations in human cancer tissue. They examined nearly 80 tissue samples from patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma to validate the results.

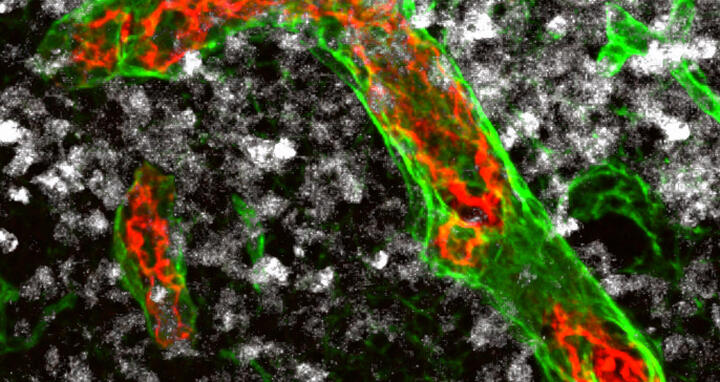

Immune cells can migrate into the lymph nodes via particularly large blood vessels – the high endothelial venules (red and green in the picture) – and destroy existing tumor cells (white). These vessels are gradually remodeled in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. This is probably why cell-based immunotherapies have so far not been effective against this type of tumor.

Cancer cells create protective niches for themselves

Our study now provides deeper insights into the methods tumor cells use to create protective niches in lymph nodes.

“Many types of tumors employ strategies to evade an attack by the immune system,” says Rehm. “For example, cancer cells develop special surface molecules or produce signaling molecules that shut down immune cells.” Little research had been done previously on how lymphomas protect themselves from the body’s defenses as they grow. “Our study now provides deeper insights into the methods tumor cells use to create protective niches in lymph nodes,” notes Rehm.

“It is crucial to know what is happening in the tumor microenvironment, especially when it comes to cancer immunotherapy, ” adds Menzel. “Only in this way can we devise strategies that enable therapeutic T cells to reach the tumor site, where they can fight the tumor directly.”

Easing immune cell immigration

The team plans to use the new findings to develop targeted strategies to halt or even reverse the process responsible for the disappearance of high endothelial venules. “One thing we are trying to do is specifically alter the vessels in the lymph nodes with the help of various drugs,” says Rehm. The goal here, he says, is to ease immune cell immigration and prevent tumor cells from shielding themselves against attack in their niches. In this way the researchers hope that immunotherapeutic approaches like CAR T-cell therapy may also become more effective against aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.

Text: Anke Brodmerkel

Further information

Literature

Lutz Menzel et al. (2021): „Lymphocyte access to lymphoma is impaired by high endothelial venule regression“. Cell Reports, DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109878

Downloadable image

Immune cells can migrate into the lymph nodes via particularly large blood vessels – the high endothelial venules (red and green in the picture) – and destroy existing tumor cells (white). These vessels are gradually remodeled in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. This is probably why cell-based immunotherapies have so far not been effective against this type of tumor. Photo: AG Rehm, MDC

Contacts

Dr. Armin Rehm

Head of the Translational Tumor Immunology Lab

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

+49 30 9406-3817

arehm@mdc-berlin.de

Jana Schlütter

Editor, Communications Department

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

+49 30 9406-2121

jana.schluetter@mdc-berlin.de or presse@mdc-berlin.de

- Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

-

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) is one of the world’s leading biomedical research institutions. Max Delbrück, a Berlin native, was a Nobel laureate and one of the founders of molecular biology. At the MDC’s locations in Berlin-Buch and Mitte, researchers from some 60 countries analyze the human system – investigating the biological foundations of life from its most elementary building blocks to systems-wide mechanisms. By understanding what regulates or disrupts the dynamic equilibrium in a cell, an organ, or the entire body, we can prevent diseases, diagnose them earlier, and stop their progression with tailored therapies. Patients should benefit as soon as possible from basic research discoveries. The MDC therefore supports spin-off creation and participates in collaborative networks. It works in close partnership with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin in the jointly run Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). Founded in 1992, the MDC today employs 1,600 people and is funded 90 percent by the German federal government and 10 percent by the State of Berlin.