Completing a PhD must be celebrated

A successful doctoral thesis is the crowning achievement of an outstanding performance in research. It is also testimony to the hard work, discipline, and perseverance shown by the author over the past years. This year, eleven PhD students at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) achieved this goal. On September 16, their doctoral degrees were celebrated and conferred at a graduation ceremony in the large conference hall of the MDC’s Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology.

In previous years, the role of master of ceremonies was played by Prof. Michael Gotthardt, head of the Neuromuscular and Cardiovascular Cell Biology Lab. He kicked off the festivities by passing the baton – together with a bouquet of flowers – to Dr. Hanna Hörnberg, whose MDC research group focuses on the molecular and cellular basis of behavior. In her opening speech, the neuroscientist addressed the demanding and challenging nature of a PhD, saying how it can drive aspiring candidates to self-doubt and even despair. But above all, she focused on the positive and fulfilling aspects of the experience: gaining research experiences and new skills, sharing knowledge, and working with like-minded people in an inspiring environment. This can become quite overwhelming, she admitted, when you are finally recognized as an expert in your field – an achievement the PhD students at the Max Delbrück Center are well on their way to achieving, as was shown by one of her slides: an impressive list of publications that the young scientists have made a significant contribution to as first authors.

Prof. Ntobeko Ntusi from Cape Town gave an inspiring keynote speech.

An inspiring keynote speech was then delivered by Prof. Ntobeko Ntusi, chair and head of the Department of Medicine at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and Groote Schuur Hospital. He reminded the audience that a PhD does not end education; rather, the degree is a commitment to never stop gaining knowledge and thus self-knowledge. “Your education should enable you to always be the best version of yourself,” he said, appealing to graduates to “stand up for justice in a world increasingly marked by dwindling global solidarity.” To that end, he said, no matter how they continue on their path after graduation, they should never give up on their dreams. And they should always be kind to themselves and to others. “You will never know when a kind word can brighten or even change someone else's world,” Ntobeko Ntusi said. “The injustices of this world are fleeting, but the effect of kindness is lasting.”

A publication highlight: the chloride ion channel ASOR

If the presentation of the PhD certificates is the main ingredient of a successful graduation ceremony, the science prizes are the seasoning. This year, the winner of the MDC’s PhD Publication Prize for the best paper was Mariia Zeziulia from the Thomas Jentsch Lab, who researches the physiology and pathology of ion transport at the Max Delbrück Center and the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP). She was awarded first-place prize money of €1,000 provided by the Dr. Pritzsche Foundation. Her paper, which was published in Nature Cell Biology, focuses on the chloride ion channel ASOR. Jentsch’s group discovered the molecular identity of this channel in 2019 and set out to pinpoint its purpose.

Mariia Zeziulia (left), a doctoral student in Prof. Thomas Jentsch’s lab, took first place in the PhD Publication Prize competition.

In the most recent study, the researchers learned that it significantly influences immune and cancer cells. In order to grow, our cells “feed” by taking up water, salts, and nutrients from their environment via vesicles – small fluid-filled sacs that bud inwards from the cell membrane. This process is called macropinocytosis and occurs in practically all cells, but is particularly pronounced in tumor cells and specialized immune cells called macrophages. In order for the cells to be able to process what they take in via the vesicles, these have to shrink, which requires them to expel water, the process which can happen only after Sodium ions and Chloride ions leave the vesicle first through the membrane proteins known as ion channels. ASOR plays a key role here, because when ASOR is removed, the vesicles do not shrink. In such case the recycling of the cells’ surface proteins, for example the signal receptors, becomes significantly slower. Such a delay in receptor recycling leaves the macrophages less responsive to signals from their surroundings, that can impair their immune functions. Tumor cells, on the other hand, benefit: less shrinkage means more protein fragments remain inside the tumor cells due to lower recycling rate, that results in more proteins being available for the tumor cells to feed on and grow.

Second place in the PhD Publication Prize competition is endowed with €500 and is sponsored by the Society of Friends of the Max Delbrück Center. This year, it was awarded jointly to Laura Corradi from the Cardiovascular-Hematopoietic Interaction Lab led by Dr. Suphansa Sawamiphak, and to Sara Lelek-Greskovic from the Electrochemical Signaling in Development and Disease Lab led by Dr. Daniela Panáková.

How neurons calm themselves down

The presentation of degrees and awards was followed by beverages, hors d'oeuvres, and conversation.

Laura Corradi has been researching a topic that most PhD students are only too familiar with: stress. Though stress may sound burdensome at first, the heightened state of alert it puts the body in has a function that is vital for survival: it helps us deal with or overcome threats. It is well known, however, that chronic stress can trigger panic attacks and lead to depression or burnout. Up to now, the mechanisms that determine the extent of the stress response have been unclear.

Corradi discovered neurons in the hypothalamus of zebrafish larvae that are activated in situations of stress. The hypothalamus is a region in the brain that regulates autonomic and hormonally controlled processes including breathing, circulation, body temperature, and sex drive. When these neurons are activated, the hypothalamus produces cortisol – the primary stress hormone in both fish and humans. The neurons themselves secrete a peptide called galanin, which they use to keep themselves in check. It seems that, in this way, they calm the fish larvae and prevent them from overreacting to stress. Together with her colleagues and researchers from the Padova Neuroscience Center at the University of Padua in Italy, Corradi has now presented her findings in the scientific journal Current Biology.

The self-healing powers of zebrafish hearts

The co-runner-up Sara Lelek-Greskovic has been studying the regenerative tricks of zebrafish, which can repair organs – including their hearts – without leaving any scar tissue. This means that, unlike humans, the heart’s pumping capacity is unimpaired following a heart attack. To find out how the little fish does this, the scientists simulated myocardial infarction injuries on a zebrafish heart. They held a cold needle to the fish’s heart, immediately killing any tissue that was touched. Initially, a scar formed from fibroblasts – the cells of the skin that provide its structure. In humans, the process stops at this point. In the zebrafish heart, however, the researchers discovered new fibroblast variants that temporarily enter an activated state. They read genes that are responsible for forming proteins, including connective tissue factors like collagen 12. The researchers used single-cell analyses and cell lineage trees to track the regeneration of the heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes). They published their observations in the journal Nature Genetics.

The beauty of science

Prof. Michael Gotthardt (right) is passionate about photography. Here he presents a camera to Ehsan Tasbihi, the winner of the Best Scientific Image Contest.

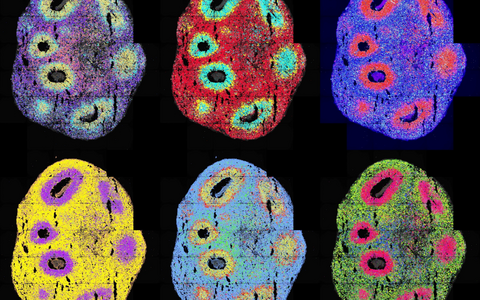

After the Publication Prizes had been awarded, the winners of the Best Scientific Image Contest were announced. Once again, the selected works illustrated that science is far from monochrome. Ehsan Tasbihi from Prof. Thoralf Niendorf's Experimental Ultrahigh-Field MR Lab won first prize – a Nikon Coolpix B500 – with his picture “Andy Warhol Kidney”: a series of images of a rat kidney in vibrant pop-art colors obtained from the magnetic resonance imaging of the tissue. The image’s extremely high resolution allowed the complex morphology of the kidney – including the cortex, medulla, and renal pelvis – to be seen very clearly.

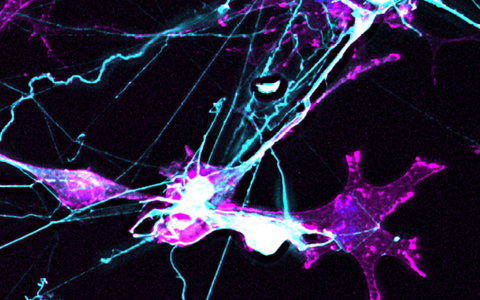

The second-place prize of €200 went to Silke Frahm-Barske. Her image of brain cells produced from human stem cells was created within the Pluripotent Stem Cell Core under the direction of Dr. Sebastian Diecke and shows how neurons communicate with glial cells. Using the technique of immunostaining with fluorescent antibodies, she succeeded in capturing a picture that is reminiscent of a lightning storm flashing across a blue-black night sky.

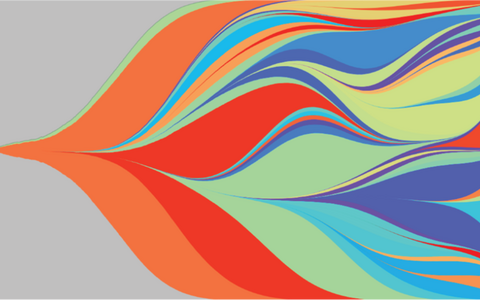

The jury could not decide on the third-place winner, so they awarded it jointly: Adam Streck from Dr. Roland Schwarz’s Evolutionary and Cancer Genomics Lab received €100 for his colorful diagram that illustrates the growth process and constantly evolving mutations of a tumor over several years. It was created with the help of the high-performance simulation program SMITH, which was developed by the research group. Another €100 went to Ivano Legnini from Prof. Nikolaus Rajewsky’s Systems Biology of Gene Regulatory Elements Lab. His picture is called “Six little eggs,” and looks just like a group of colorful Easter eggs on a black background. The “eggs” are in fact brain organoids derived from human stem cells, with colored dots that are messenger RNA molecules. The patterns arise because different cell types produce different colors.

Text: Jana Ehrhardt-Joswig